The perception of time is closely linked to what we experience as the present.

The Now

We humans do not perceive the present as a tiny point on a timeline between past and future, but rather as a period of a few seconds. We refer to this period as present. Within this period of time, our brain continuously builds a holistic model of reality from our sensory perceptions, which we experience as the present.

How do we perceive time?

To build and constantly update this mental model of our environment, our brain performs an incredible task. It must quickly combine light, sound, temperature, smells, and tactile sensations to create a coherent overall picture.

Even individual senses, such as seeing or hearing require extremely complicated processes to take place in the nervous system and brain. For example, when you hear someone say the word “present,” you do not perceive it as a sequence of individual sounds like:

p – r – e – s – e – n – t

Instead, your brain recognizes the coherent word “present.” To achieve this, it must process the sound waves of each letter, identify them, combine them into a single word, and distinguish them from the previous and next words. Additionally, it must determine the meaning of the word.

The brain uses a short-term memory for all of this. This memory lasts for about three seconds and ultimately determines how much time our brain has to model the present.

Thus, the present we perceive is the three seconds that have just passed.

All together

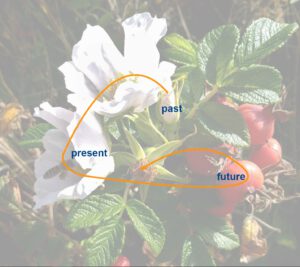

These are precious, rare moments in which the connection between past, present and future suddenly becomes visible to us. The following picture is an example of this. Here we see budding, blooming, pollination, ripening and wilting all at the same time in one single wild rose. Symbol of past, present and future:

How do physicists see time?

Surprisingly, physicists still do not fully understand what time actually is. Aristotle provided an insightful definition of time long ago. Newton introduced a completely different concept that has shaped our understanding of time to this day (see the diagram at the top).

Einstein later integrated Aristotle’s and Newton’s concepts with his theory of spacetime. His idea worked well for some time until quantum physics complicated matters. Since then, physicists have been trying to develop a new model of time—true to the motto “still confused but on a higher level.” If you want to explore these ideas in detail, I recommend reading “The Order of Time” by Carlo Rovelli.

Fortunately, physicists’ problems with time are only relevant in situations that we are never exposed to. For example, the question of whether our present is the same “now” as on a planet light years away. As long as we don’t want to compare our calendar with an alien, we can stick to our familiar Newtonian definition of time.

More challenges

Vision is even more complicated. There is the reception of light waves by two eyes, the pre-processing of the images in the individual eye and the assembly of a spatial image. Of course, this also includes the correct positioning of the image in space, with the brain automatically taking into account the tilt of the head with the help of the sense of balance and the tension of the neck muscles. To do this, information of several senses must be processed in combination. In fact, our brain always includes all senses when modeling the present.

Our brains face additional challenges as well. Many external stimuli do not initially fit together seamlessly; for example, light stimuli reach our brains much faster than sound stimuli.