Page Contents

Why this camera makes me smile

This tiny camera looks like a jewel and is very robust at the same time. The Riga Minox or Minox I was invented 90 years ago and still works today like the first day. It makes me smile that I can simply insert a film into this camera today and take photos with it. Photos like these.

The Riga Minox is the most amazing of all Minox cameras. It was created from scratch by a single person in 1935. This first design already had all the essential features of the later models. It was the big hit, the Turning Point, as the title of the first advertising brochure read. The philosophy of this camera is best documented in this brochure. The following statements in “” are taken from this booklet and can therefore be considered the authentic design goals of the inventor.

Entirely new principles

The overarching goal was “a camera to be devoid of the intricacies of operation inherent in precision cameras but at the same time to be capable of superlative work”.

“Above all, the camera had to be reduced in size … that it could be slipped into the smallest handbag or the ticket pocket without being noticed.”

“It had to be sympathetically responsive to all photographic situations and yet so simple that no technical knowledge or skill would be necessary for its operation.”

“An elegant companion, like a fine watch, for sophisticated ladies and gentlemen to carry and use to record the events of their daily lives.”

No wonder that its artistic design has earned it a place in the Museum of Modern Art.

Extreme handiness

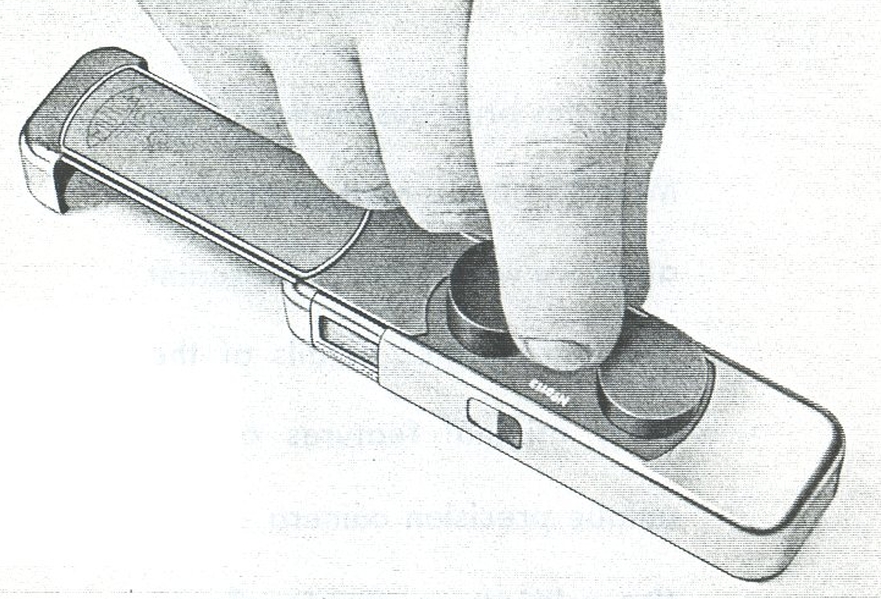

“A light lengthwise pull prepares the camera for action. All that remains to be done is to press the button.” Since there is no aperture to set, only the exposure time and the distance need to be set. With the exposure latitude of the black and white films of the past and the color films of today, a rough estimate of the brightness is sufficient. This can often be left unchanged.

The distance setting is only necessary for subjects closer than 2 m. The depth of field is displayed. But then the Minox shows its strengths, as it can focus down to 0.2 m. At the same time, the automatic viewfinder ensures that you see always the correct image section even in close-ups.

Maximum convenience

The camera weighs only 135 g in total (own measurement) and fits securely in the hand when unfolded when taking photos.

“An exclusive Minox feature is the automatic winding-on of the film after each exposure … The short lengthwise movement which extends the body of the camera to the working position simultaneousely sets the camera in readyness for taking the picture. The shutter is set and the film moved forwards and pressed against the picture aperture. Externally the lens and the view-finder are uncovered, these four operations achieved automatically when the camera body is extended. … When opening or closing the Minox, the fingers may remein in the same position as for the actual taking of the picture.”

The idea of providing the film in a film cartridge with two chambers was completely new. “For daylight loading – you simply slide the panel on the reverse of the camera, remove the exposed magazine and insert a new one”. This principle was only taken up many years later and became widely known through the Kodak 126 instamatic film in 1963.

Smallest format

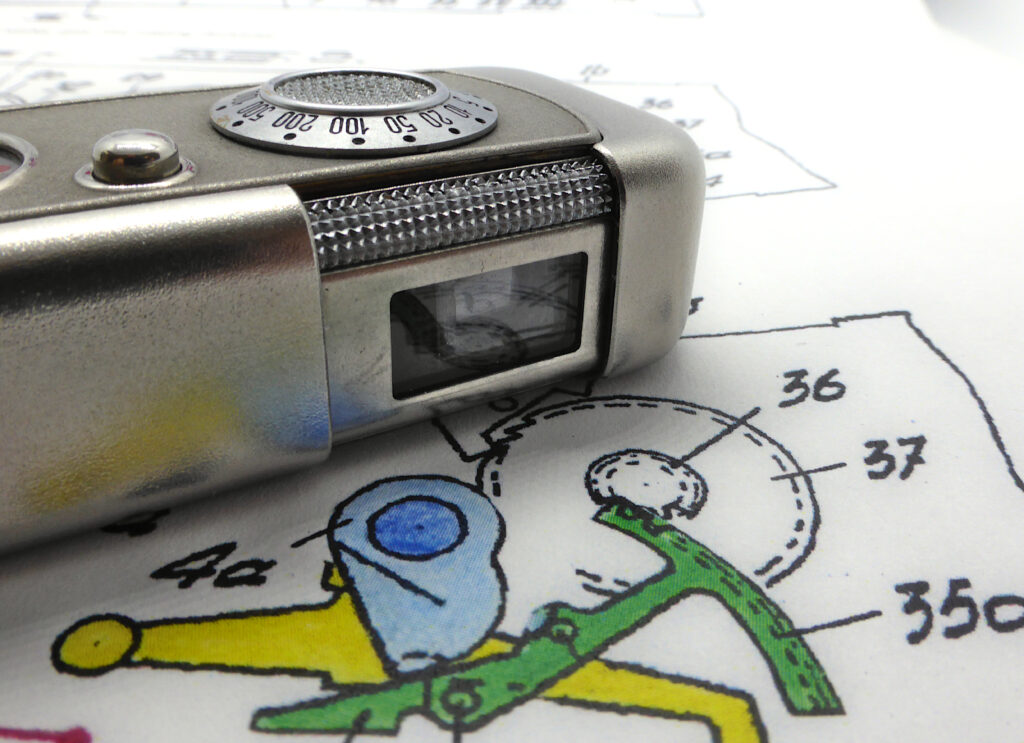

“The complete camera is a slim case with no exposed optical parts and free from extruding accessories.” The housing is made of extremely robust stainless steel. In contrast to the successor models made of aluminum, there is hardly any risk of dents and scratches even with rough handling.

You have to bear in mind that the Leica was considered a pocket camera at the time, which is why its designer Oskar Barnack called it the “Lilliput camera”. It was preferred because of its small size by those photographers who wanted to have the camera with them at all times and be ready to shoot quickly. This had been the reason for the Leica’s great success. For Walter Zapp, however, the Leica was still far too big. To get an idea of the actual difference in size, we can see both cameras (Riga Minox and Zorki, a Leica clone) side by side:

This shows the degree of miniaturization achieved by the Minox compared to the Leica.

The Riga Minox construction

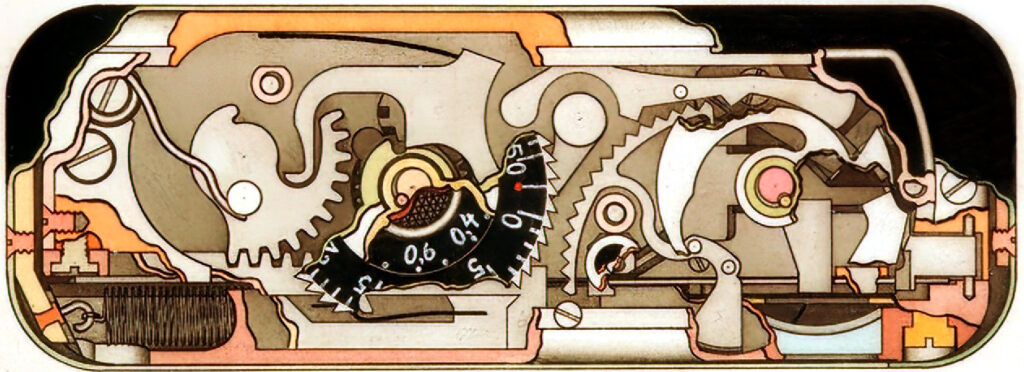

In order to achieve the above-mentioned goals, especially ease of use, the internal construction had to be even more sophisticated.

“Miniature cameras for very small pictures have been constructed before, however they were not based on new principles… Therefore ist was necessary to design and develop an entirely new type of camera… This demanded that considerable technical difficulties had to be overcome because the smaller the camera, the greater the need for precision in each and every component.”

The principle of a camera had to be completely rethought because there was nothing comparable. There were various small cameras on the market, but these were just miniature versions of the known designs. With the Riga Minox, everything that had existed before was questioned and amazing solutions were found. The most striking is the pulling apart to transport the film and cocking the shutter. This principle was still used 40 years later in pocket cameras.

It was a unbelievable constructive achievement to imagine in his brain three dimensionally the mechanisms of distance setting with coupled pivoting viewfinder, the escapement with 1/2 s to 1/1000 s, the shutter and the film transport all crammed together in a tiny housing.

The lens

“The short focal length of the Minox (15 mm) makes it possible without any special attachment to photograph objects of a distance of only 20 cm from the lens.”

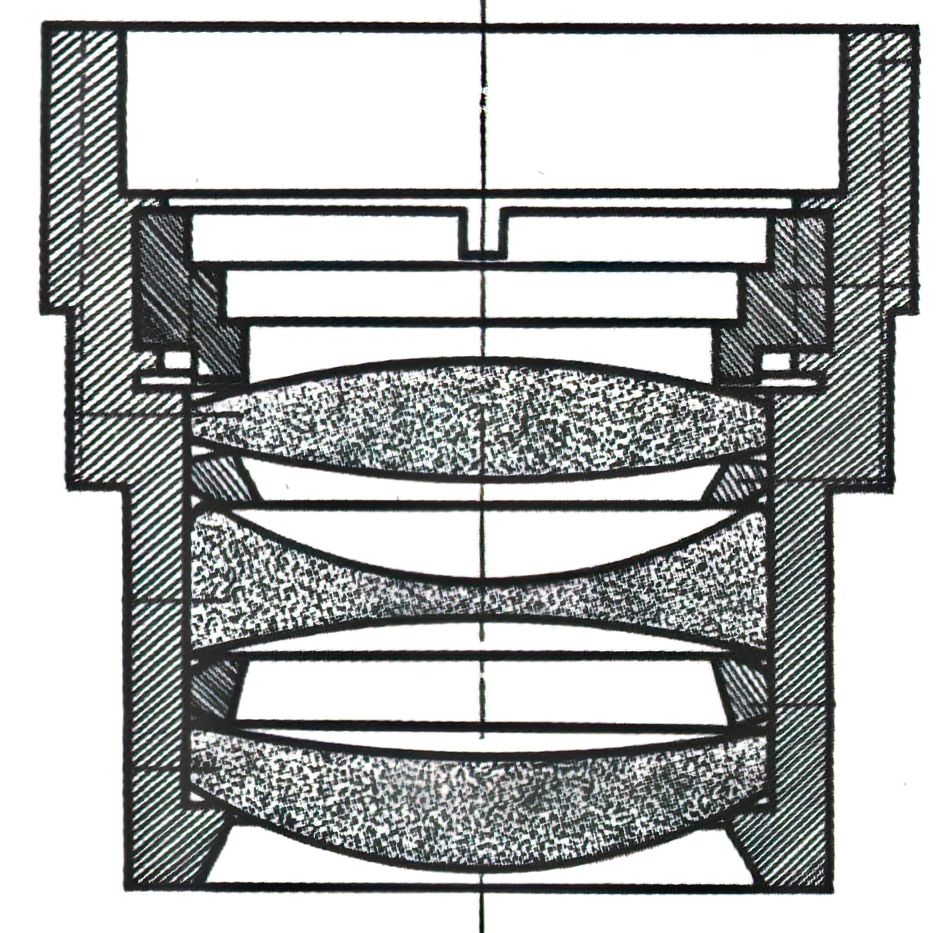

The Minostigmat is a very well-made lens. It was probably the smallest three-lens system for a camera at the time. Producing this tiny size with the uncompromising quality required was a major challenge for the manufacturer. The lens is 4.3 mm in diameter and is both compact and lightweight, matching the design of the Minox camera design.

The Minostigmat designed for the Riga Minox has some specific features:

- It is a classic Cooke triplet that corrects chromatic aberration as well as astigmatism and distorsion.

- The focal length is 15 mm (equivalent to about 45 mm in 35mm film format), which is the normal angle of view of the human eye.

- Fixed aperture of f/3.5

- Like the other camera parts, the lens was manufactured by VEF itself.

The lens is amazingly good compared to the COMPLAN of the successor model, the Minox A III.

The shutter

“The Minox camera is the first to have a lens shutter up to a 1/1000 s. This unique facility is rendered possible by the fact that the moving parts are so small. … It should be noted that the time of exposure can be set or varied while the camera is either open or closed as well as before or after the shutter has been released.”

This guillotine shutter works – at least with my Riga Minox – reliably even after so many years. To understand this ingeniously simple construction, read my article here, which shows all the phases from triggering to opening to closing the shutter with graphic illustrations.

The shutter of the Riga Minox works according to a different principle and is also constructed completely differently from all other successor models, e.g. the Minox A IIIs.

A success story

All of these ideas and designs of one single man resulted in a fully functional prototype within just one year, which was ready for production within another two years without major changes. In this way, the first Minox was brought onto the market on April 12, 1938.

Nearly all of the standard features of the 8×11 Minoxes to follow—tiny size, push-pull film-advance/shutter-cocking, focusing from 8 inches to infinity with a f/3.5 15mm lens, speeds up to 1/1000th of a second, drop-in cassette loading, viewfinder parallax correction, built-in filter—were already present in these first model. The two significant improvements (lens and shutter) were introduced by Zapp for the successor model in 1949 and remained unchanged until the last model in 1994, the Minox AX.

Production of the Riga Minox

The camera was manufactured by Valsts Elektrotehniskā Fabrika (VEF, State Electrotechnical Factory) in Riga, which had been founded in 1919. In the period from 1938 to 1944, a total of approx. 17,500 Minox were produced and very well received by the market, for example in the UK. The retail price in the USA was 79 $ in 1940. That corresponds to about 1800 $ today.

The Soviet Union occupied the Baltic states from 1940 to 1941. Around 3000 Minox cameras were produced during this time. Afterwards Riga was under German occupation from 1941 to 1944. Before the Soviets 1944 invaded again Latvia, VEF employees hid a few boxes of newly manufactured Minox cameras and parts under the floor boards of VEF buildings to prevent them from falling into the hands of the occupying forces. These boxes were discovered by chance during renovation work in 1989. The cameras found were put on the market in the following years. They can be recognized by their serial numbers from the 15xxx range (source: Minox Freund 2/95). The individual parts found were assembled into cameras and also brought onto the market. They can be recognized by the serial numbers 16xxx and by the fact that they have no engraving on the film chamber cover or recent copy engravings (source: submin.com).

I therefore assume that my Riga Minox is one of the cameras found and was manufactured between 1941 and 1943. This is indicated by the serial number 15820 and the original engraving:

During the retreat from the Soviet troops in 1944, the Germans blew up the factory. After that, no more Minox were built there. Due to the turmoil of war and the past 80 years, many Riga Minox were lost. Therefore, especially well-preserved and functional Riga Minox are rare.

Taking pictures with the Riga Minox

The operation of the Riga Minox is identical to the successor model, the Minox A. The Minostigmat lens is perhaps not quite as sharp at the edges as the later four-lens Complan. Nevertheless, the results can certainly keep up with the later models.

Since the Riga Minox did not have a light meter, VEF provided an interactive table with which the exposure time could be determined. Also the manufacturer has been thinking about the best way to store Minox negatives. As early as 1938 the Minox came with special transparent celluloid sleeves for 50 negatives.

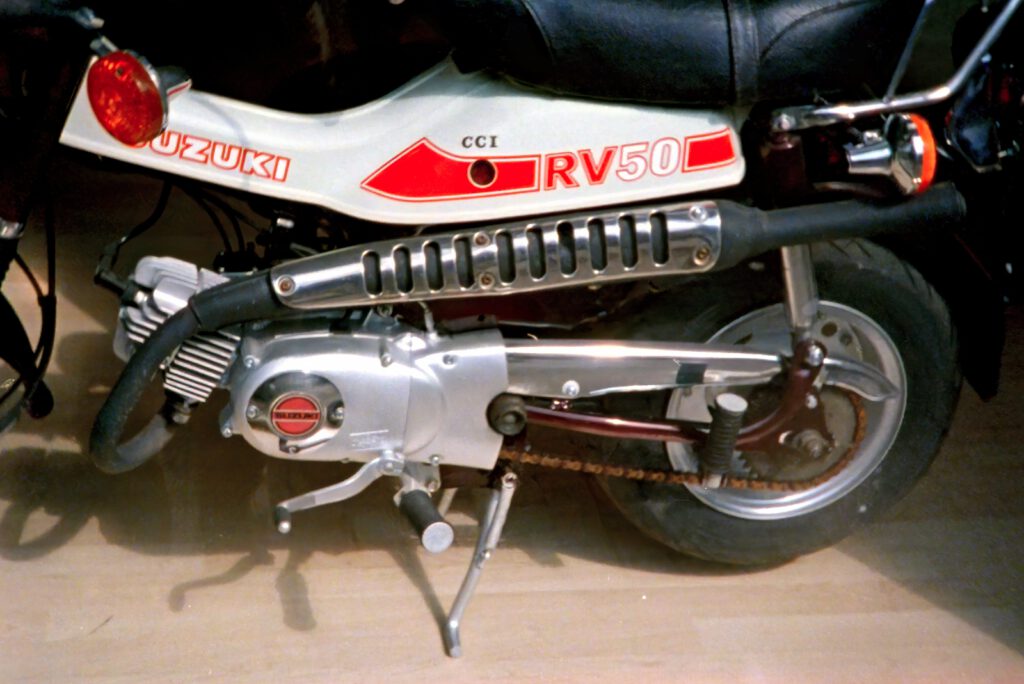

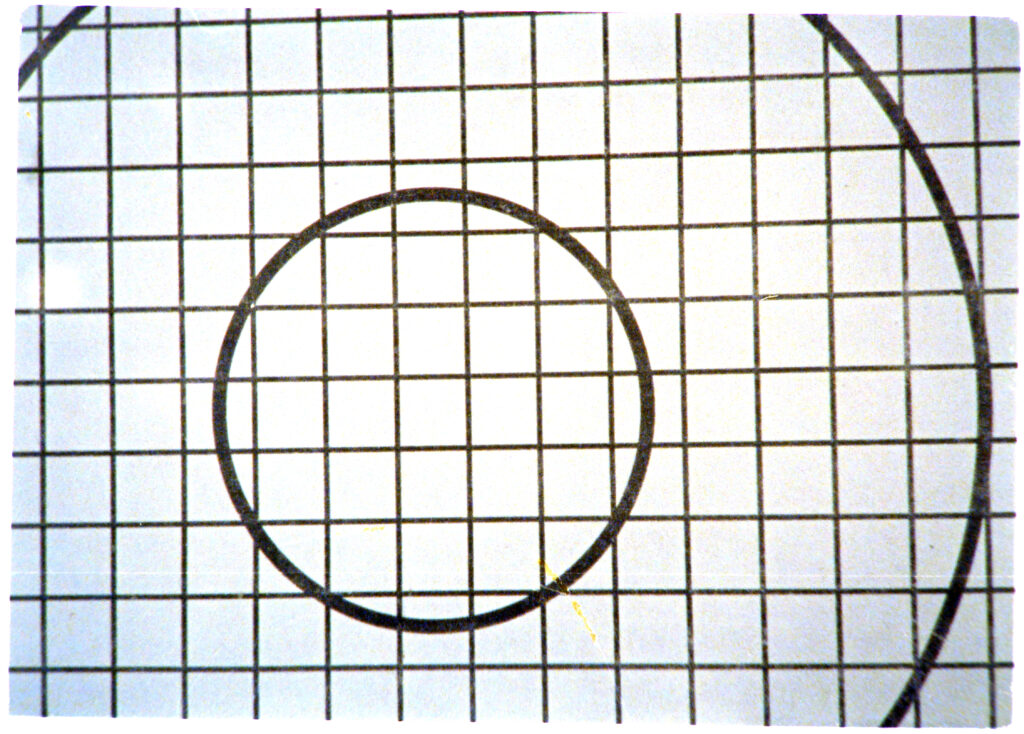

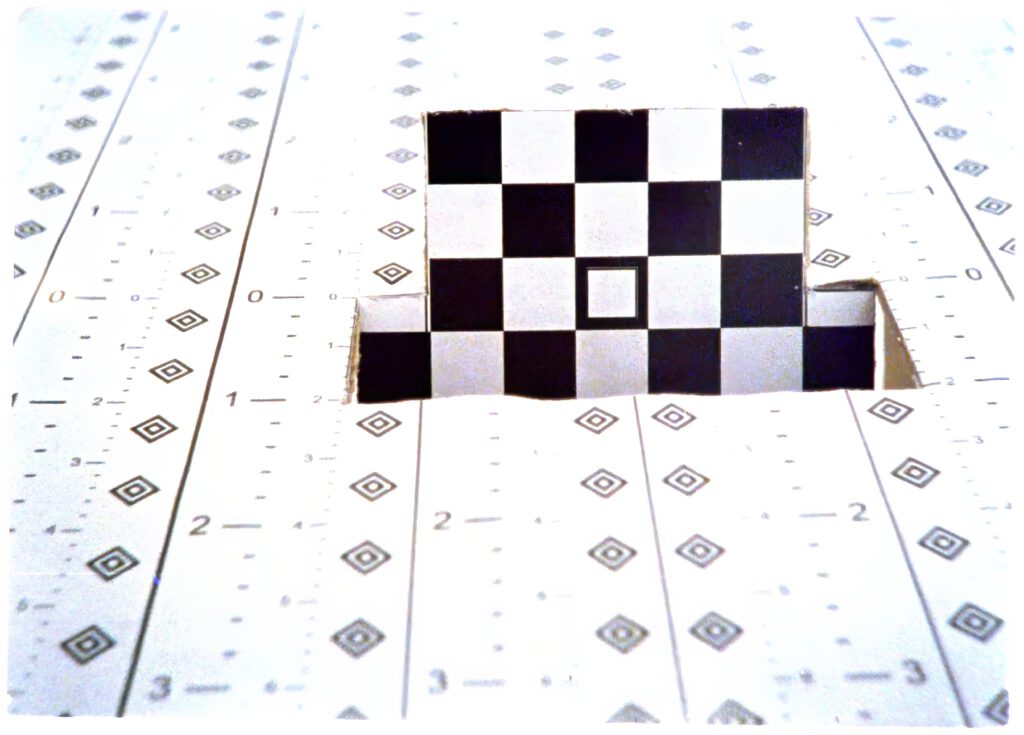

The following pictures were taken with the above Riga Minox and an Kodak Ektar 100 in 2024.

Test photos at different distances

Distance setting infinite, negative uncut. Note the sharpness as well as the natural colors, even though the lens is not coated:

Distance setting 0.2 m, negative uncut. Check the details and note the exact frame due to the automatic parallax compensation:

Distance setting 0.2 m, negative uncut, to check the lens distortion. Note the lack of distortion at the edges:

Distance setting 0.2 m, negative uncut, to test the distance setting and depth of field. Note the maximum sharpness at 0, which corresponds exactly to the set distance:

Riga Minox in a Russian prisoner of war camp

Proof of how robust and reliable the Riga Minox was is the story of Klaus Sasse, who secretly took photos of everyday life in the camp with it for two years as a prisoner of war. In Königsberg (today Kaliningrad), the German lieutenant, who had been in charge of telegraphic communications, was taken prisoner of war by the Russians in April 1945.

It seems an impossible undertaking to secretly take photographs in prison camps and keep the camera hidden from the repetitive felting. Against all odds, he managed to take 179 pictures from 4 rolls of film with 50 shots each and had them smuggled out of the camp to Germany. He knew that he would be shot immediately if the camera was found in his possession. In the following picture you can see him secretly taking a photo of himself in a pane of glass. You can clearly see the Minox.

courtesy of Waxmann Verlag, Germany ©

Without a light meter, in brief, unguarded moments, he took moving and shocking pictures. They are unique, because there are no other unauthorized photos from Soviet prisoner of war camps. He has written a detailed report on this, which has been published as a book.

courtesy of Waxmann Verlag, Germany ©

His report touched me even more than the pictures. As a German, I have previously learned first-hand from stories about the terrible treatment of Russian prisoners of war in the German Reich. Sasse describes in nuanced ways also the good treatment that he himself experienced in the Russian camps. He tells of the female Russian camp doctor who treated him better when he was seriously ill than the German doctor and fellow prisoner.

It is tragic when he tells of his Russian guards taking the prisoners’ meager food because they themselves were so hungry. The following photo shows Sasse himself in the camp’s detention cell (карцер). The photo was secretly taken through a hole in the door by a fellow prisoner with Sasse’s Minox. He is wearing a thin coat made of nettle cloth and sitting on a table to protect himself from the cold.

courtesy of Waxmann Verlag, Germany ©

He was sentenced to three days in detention for taking a handful of grains from a sack. The punishment seems very harsh for such a trivial matter. However, one must remember that one of the three largest famines in the history of the Soviet Union was taking place at that time, in which one to two million Soviet citizens lost their lives. The citizens were hardly better off than the camp inmates.

Fortunately, Sasse survived his time as a prisoner of war and was therefore able to report on his experiences. It was an extraordinary stroke of luck that he was able to take the photos and bring them to Germany. He died in 2003.

Footnote:

- Camera in Minox leather case for Flash Gun Model B ↩︎