The CIA describes the Minox, as “the world’s most widely used spy camera” noting its small size made it easy to conceal and ideal for photographing documents at close range.

Page Contents

Minox: Designed for Amateurs or Spies?

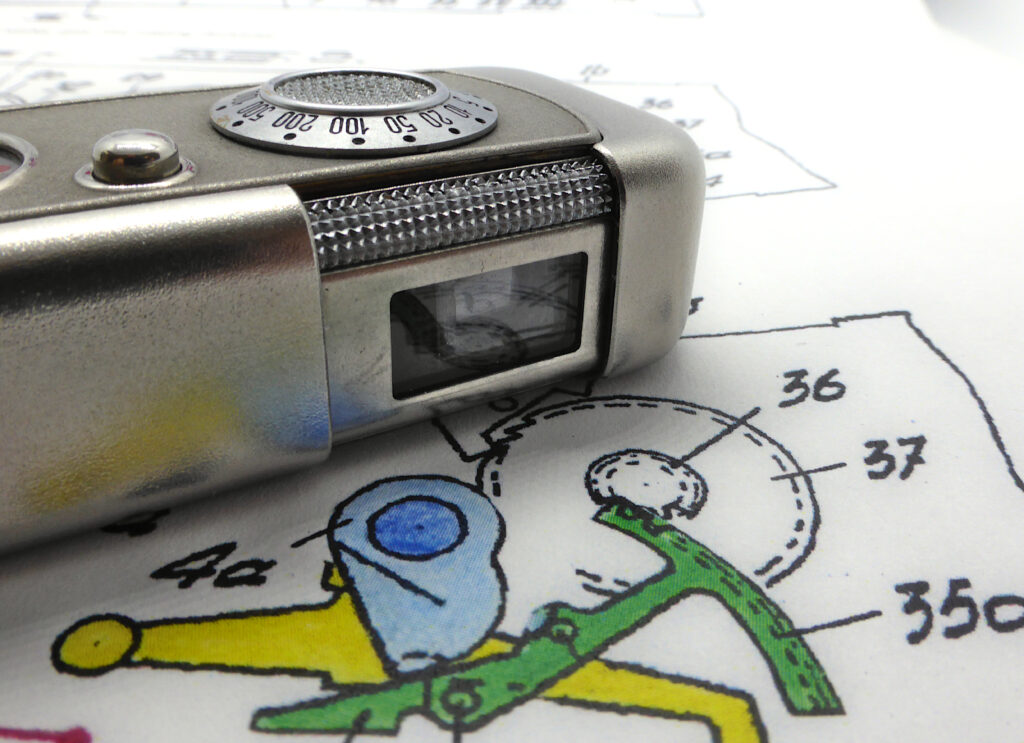

The Riga Minox, introduced in 1938 by Walter Zapp, is an iconic subminiature camera renowned for its compact size and high-quality optics, capable of producing sharp images on 8×11 mm film. While its legacy as a “spy camera” is cemented in Cold War history, the question remains: was the Minox Riga originally designed for amateurs and travelers, or was it intended for espionage?

What does the Minox advertisement say?

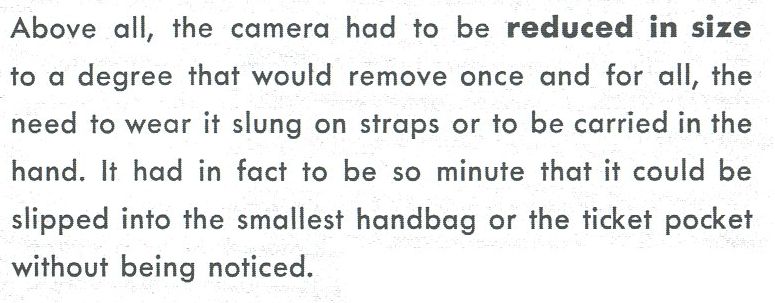

A promotional brochure by VEF, The Turning Point on the Riga Minox from 1938 is very informative. At this time, Zapp was solely responsible for everything concerning his baby, the Minox. It can therefore be assumed that this brochure accurately reflects his real intentions in the development of this camera.

According to The Turning Point the Riga was conceived to provide “a camera so small it could always be carried, yet capable of producing high-quality images for amateurs and travelers.” Walter Zapp envisioned a portable device for everyday use, ideal for capturing spontaneous moments on the go. Its lightweight body and ability to take up to 50 exposures per film roll made it appealing to hobbyists, tourists, and professionals needing discretion, such as journalists.

However, the camera’s compact design, macro capabilities (focusing as close as 20 cm corresponds to a 98 x 135 mm frame), and precision engineering quickly caught the attention of intelligence agencies. By 1942, the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS) purchased 25 Minox cameras, as noted in a public record (Wikipedia), signaling its early adoption for espionage.

What does the inventor say?

The Riga’s dual appeal—marketed to civilians but coveted by spies—reflects its versatile design. While Zapp’s intention, as per The Turning Point, was to democratize photography for amateurs, the camera’s concealability and ability to photograph documents with clarity made it a natural fit for covert operations. The first buyer of the Riga Minox was a diplomat. “Unfortunately, I realized immediately that it was

espionage!” Zapp later said in an interview. He was not enthusiastic about it, which suggests that this was not the intended use.

This duality set the stage for its widespread use by notorious spies cementing the Minox Riga’s reputation as a tool that bridged the worlds of leisure and espionage.

A Tool of Cold War Espionage

The Minox subminiature camera, developed by Walter Zapp in 1936, became a legendary tool in Cold War espionage due to its compact size, high-quality optics, and ability to discreetly photograph documents. Measuring smaller than a cigar and capable of producing sharp images with its 8×11 mm film, the Minox was a favorite among spies.

This article chronicles the use of a Minox spy camera by five of the most notorious figures in Cold War espionage: Heinz Felfe, Oleg Penkovsky, Günter Guillaume, John A. Walker Jr and Guy Binet. Their stories, spanning the 1950s to 1980s, highlight the Minox’s pivotal role in intelligence operations.

1950–1961: Heinz Felfe, BND officer and KGB double agent

Heinz Felfe was a German intelligence officer whose case stands as one of the most significant espionage scandals of the Cold War, particularly due to his extensive use of the Minox camera. Felfe was a senior officer in the West German Federal Intelligence Service (BND) but secretly operated as a double agent for the Soviet KGB. His espionage activities, spanning over a decade, caused substantial damage to Western security, and the Minox camera was a critical tool in his covert operations.

Felfe utilized mainly the Minox A camera to photograph thousands of classified documents, which he then passed to his Soviet handlers. Felfe’s use of the Minox A began in the early 1950s and continued until his exposure in 1961. He photographed sensitive materials, including military plans, intelligence reports, and communication logs, storing the images on Minox films.

Felfe’s treachery had profound consequences for Western security. Over his 11-year tenure as a double agent, he compromised thousands of documents and revealed the identities of numerous Western agents, leading to their arrest and, in some cases, execution in the Soviet Union. His actions undermined the BND’s operations and strained relations with allied intelligence services, marking his case as one of the most damaging espionage scandals of the Cold War.

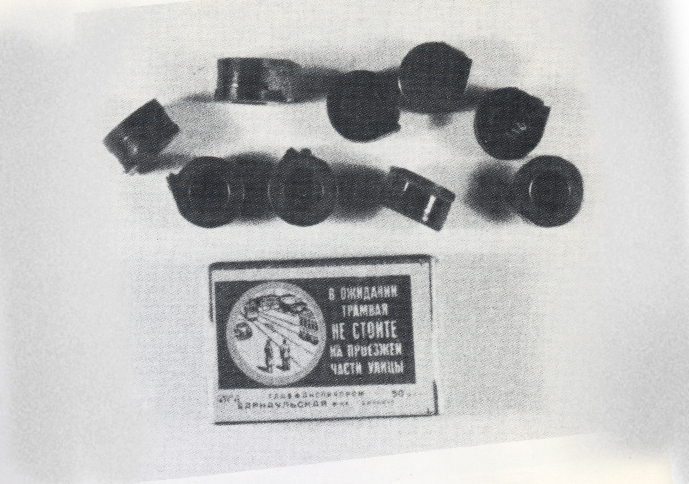

On November 6, 1961, he was arrested at the BND headquarters in Pullach, West Germany. At the time of his arrest, authorities discovered a dozen Minox films in his briefcase, containing incriminating evidence of his espionage activities. Reports indicate that, in a desperate attempt to destroy evidence, Felfe tried to swallow one of the Minox films during his arrest, but quick intervention by the arresting officers prevented this.

1960–1962: Oleg Penkovsky and the Cuban Missile Crisis

Oleg Penkovsky, a Soviet military intelligence officer, became one of the CIA’s most significant assets in the 1960s. Volunteering to work with the US and UK, he provided crucial intelligence on Soviet military plans and weapon systems. His information was vital during the Cuban Missile Crisis, revealing whether Soviet missiles were operational and detailing technical specifications e.g. the field manual of the R12 Dvina (SS4) rocket.

Oleg Penkovsky, a Soviet GRU colonel, became one of the West’s most valuable double agents, operating for the CIA and MI6 under codenames IRONBARK and HERO.

From 1960 to 1962, Penkovsky used a Minox B camera to photograph thousands of classified Soviet documents, providing critical intelligence during the Cuban Missile Crisis. His photos, which included details of SS-4 and SS-5 missile systems, helped the U.S. verify Soviet capabilities and avert a nuclear conflict.

Penkovsky’s compact camera allowed him to work undetected in Moscow, passing films via dead drops to contacts like Janet Chisholm. Declassified CIA documents confirm his extensive use of the Minox:

“In Wynne’s room at the Metropol, Penkovsky had turned over film and sever- al packets of highly classi- fied information from the Kremlin files, as well as a broken Minox camera (he had dropped it during one of his nocturnal photogra- phy sessions). Wynne had given him a replaeement camera and the little box of candy lozenges to use in the contact with Mrs. Chisholm.” (CIA-RDP75-00149r000600260009-2)

In the Soviet trial against him, the material found in Penkovsky’s apartment was listed as evidence: “During the search of Penkovsky’s apartment … the following items were discovered … three Minox cameras and a description of them … 15 unexposed rolls of film for the Minox camera …” (CIA-RDP75-00149R000600260014-6)

Before Minox films were passed on, it was common practice in espionage to separate the take-up spool with the exposed film from the cassette. This made the container to be transported even smaller, see photo on the right.

While the aerial photographs taken during the U2 flights over Cuba merely showed that missiles had been installed, Penkovsky’s documents made it possible to identify the missiles and assess their operational readiness:

“On October 18, 1962, the Central Intelligence Agency released a “Joint Evaluation of the Soviet Mission Threat in Cuba,” based on intelligence obtained as of 9 p.m. that day. The evaluation, prepared by the Guided Missile and Astronautics Committee, the Joint Atomic Energy Intelligence Committee, and the National Photographic Interpretation Center, was codenamed Iron Bark because it drew upon intelligence material provided by the Central Intelligence Agency’s important Soviet source, Colonel Oleg Penkovsky. It was based on “relatively complete photo interpretation of U-2 photography” made on missions of October 14, and two on October 15 and “very preliminary and incomplete readout” of coverage of six U-2 missions on October 17. The evaluation concluded that there was “at least one Soviet regiment consisting of eight launchers and sixteen 1020-nm (SS-4) medium-range ballistic missiles now deployed in western Cuba at two launch sites.” These mobile missiles had to be considered operational and could be launched within 18 hours after the decision to launch was made.” (Office of the historian)

Penkovky’s espionage ended with his arrest by the KGB in 1962 and execution in 1963, but the Minox B’s role was pivotal in delivering intelligence that shaped the Cuban Missile Crisis outcome.

1970–1974: Günter Guillaume and the Fall of Willy Brandt

Günter Guillaume, an East German multilaterali operative, infiltrated the West German government as a trusted aide to Chancellor Willy Brandt from 1970 to 1974. Stationed in Bonn, Guillaume used Minox cameras — likely Minox B and C—to photograph sensitive government documents, passing them to the Stasi (“Staatsicherheit”, Ministry for State Security). The Stasi’s Main Reconnaissance Administration, Operative Technique (HV A VIII) referred to the Minox by the code name “Jupiter”.

Guillaume’s exposure in May 1974 triggered a political scandal that led to Brandt’s resignation, marking a significant blow to West German politics during a period of détente.

The Minox C (1969–1978) featured a slightly larger design than the B but retained the 8×11 mm film format and macro capabilities, making it ideal for Guillaume’s covert work in the secure environment of the Federal Chancellery. Historical sources confirm his use of the Minox:

“Among the people who reportedly used Minox is Günter Guillaume, a spy from FDR who had infiltrated the office of the West German Chancellor Willy Brandt. Guillaume’s exposure in May 1974 ultimately led to Brandt’s resignation.” (LSM.lv)

Guillaume’s Minox photography enabled the Stasi to gain insights into West German policy and NATO strategies. His arrest and conviction, followed by a spy swap in 1981, underscored the Minox’s effectiveness in high-stakes espionage.

A Minox advertisement from 1975 flirts with the Guillaume case and writes:

BEFORE WE DISCUSS THE DISTANCE DIAL, JUST ONE MORE WORD ABOUT THE MESSRS. GUILLAUMES.

If we believe the news agencies and the criminal police, there are a few thousand spies in German industry and German politics. We can therefore state with certainty:

ALMOST EVERY SPY HAS A MINOX, BUT NOT EVERYONE WHO HAS A MINOX IS A SPY.

A fact that is corroborated by the fact, that we have sold many more Minox cameras than there are spies. Nevertheless: It cannot be denied that anyone with the Minox C can approach an document within 20 centimeters. Anyone! And it also cannot be denied that the parallax compensation ensures that even at close range to the object, the letterhead of a letter appears untrimmed on the film.

John A. Walker Jr., a U.S. Navy communications officer turned Soviet spy, operated one of the most damaging espionage rings in American history from 1967 to 1985.

Using a Minox C and LX camera, Walker photographed cryptographic materials, naval communication codes, and classified documents, passing them to the KGB. His actions compromised U.S. national security, enabling the Soviets to decrypt sensitive communications.

The Minox C, with its improved electronics and compact design, was well-suited for Walker’s covert photography. He photographed documents at naval bases and passed films through dead drops, often involving his family and associates, including his brother Arthur, son Michael, and friend Jerry Whitworth. The CIA confirms his use of the Minox: “The world’s most famous spy camera, the Minox, was used to great effect by Soviet spy John Walker, who used a Minox C to photograph documents and ciphers.” (CIA Museum)

Walker’s espionage continued until his ex-wife reported him to the FBI in 1985, leading to his arrest and life imprisonment. His use of the Minox C highlights the camera’s longevity in espionage, extending into the 1980s.

1986-88: Guy Binet and the troubles in Zaire

Colonel Guy Binet, serving in the belgian Air Force, came under scrutiny by the Soviet military intelligence agency, the GRU, during his participation on September 26, 1983 in a cultural and themed event hosted by the “Belgo-Soviet Friendship Association.” In 1989 he was accused of passing sensitive military plans, including details of a potential intervention in Zaire, to the Soviet Union’s GRU. Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, was formerly a Belgian colony. Economic and political conditions there were so poor in the mid-1980s that the Soviet Union feared military intervention by the Belgian government. Binet allegedly met with Soviet officers in 1985 and 1986 to deliver these secrets.

He used a Minox EC provided by the GRU to photograph the documents 1. Since the EC was not actually capable of taking close-up shots, the Soviet secret service had modified it accordingly. They adjusted the lens, which was factory-set to a distance of 2.5 m, to 420 mm. The viewfinder was swiveled to compensate for the parallax shift. At this distance, files could be photographed on an area of 308 x 224 mm. The depth of field was 360 to 505 mm (pointsinfocus.com). He also used a special 400 ASA black-and-white film that was so thin that a roll with 110 exposures (1.8 m long) fit into the Minox cartridge.

The Minox EC was significantly smaller and lighter than the Minox LX, which was current at the time, and also had fully automatic exposure control.

Minox spy camera: A Technological Marvel

The Minox spy camera’s evolution made it a versatile tool across decades. Its macro capabilities allowed spies to photograph documents with precision, while its compact size ensured concealability. The Minox’s prominence is further evidenced by its use in popular culture, appearing in James Bond films like On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969) and Moonraker (1979).

While Penkovsky and Guillaume relied on the Minox B and C, respectively, the Minox LX’s introduction in 1978 suggests it may have been used in later espionage, though specific cases remain less documented due to the classified nature of 1980s operations. The camera’s marketing as a “spy camera” in the 1980s amplified its mystique.

Conclusion

The Minox spy camera was a linchpin of Cold War espionage, enabling the era’s most infamous spies to photograph thousands of classified documents with profound consequences. Felfe’s Minox A photos revealed the identity of numerous Western agents, Penkovsky’s Minox B photos shaped the Cuban Missile Crisis, Guillaume’s Minox use toppled a West German chancellor, and Walker’s Minox C compromised U.S. naval security for nearly two decades.

Minox spy camera in a Soviet prisoner-of-war camp

Notably, the camera’s concealability enabled covert photography in extreme conditions, such as in a Soviet prisoner-of-war camp during World War II. There Klaus Sasse, a young German lieutenant used his Riga Minox to document conditions clandestinely. This early instance of covert use underscores the Minox’s unintended but profound impact on intelligence gathering. For further details on its use in the Soviet POW camp, visit my article.