Page Contents

Minox A, Mamiya Super 16 and Edixa 16

Three outstanding designers have developed three distinctly different products for the same market segment. The result is three extraordinary cameras. But why are they so different, and what are the differences between them? And how did I arrive at this selection?

All three are fully mechanical cameras without exposure meters. They are among the smallest and highest-quality cameras of their kind. Each follows a recognizable product philosophy and was conceived, designed, and brought to production readiness by a single designer.

The Mamiya Super 16 is the smallest 16 mm camera in the world. The Edixa 16 is the smallest 16 mm camera with the largest negative format. Launched between 1950 and 1962, they were sold in significant numbers. The Minox was sold and became known worldwide, while the Edixa was more present on the German market and the Mamiya on the US market.

The cameras were also selected with a view to their practical use today (2026), with a wide range of film materials available. This ruled out all models that only work with perforated film. This ultimately allows their photos to be compared directly with each other.

When I refer to Minox, Mamiya, and Edixa in the following, I am referring specifically to the following camera models:

- Minox A IIIs

- Mamiya super 16

- Edixa 16 M with Schneider Kreuznach Xenar f2.8

The creators

Since the three cameras under consideration were conceived and designed by highly distinguished individuals, their settings also provide important clues as to how they viewed the task at hand. It is interesting to note how strongly the personalities of the designers are reflected in the cameras:

Walter Zapp – The Visionary – Minox A

Zapp uncompromisingly subordinates everything to his idea of the smallest possible camera with the highest image quality. Logically, everything must be executed with maximum precision and perfection. He accepts the resulting high costs. Details such as the consistent spacing of the negatives on the unperforated film, the viewfinder that swivels with the distance setting, and the rounded housing without protruding parts that protects the viewfinder and lens from dust are non-negotiable for him.

Seiichi Mamiya – The Pragmatist – Mamiya super 16

Mamiya focuses on what is feasible and finds ingeniously simple solutions that result in user-friendly and robust designs. He follows classic engineering principles by striving for high quality while always keeping an eye on costs. For example, he does not take miniaturization to extremes, but opts for a simple design that is extremely robust and easy to maintain. If you look closely, you will find original and well-thought-out details everywhere, such as the arrangement of the three (!) housing screws on the underside, which allow the camera to stand on any surface without wobbling.

Heinz Waaske – The technology enthusiast – Edixa 16

Waaske suggests that he had great fun solving technical problems. Although he developed many camera models, including some very successful ones as the famous Rollei 35, he himself did not particularly enjoy photography. He probably preferred to indulge in his world of technical precision engineering, where he sought his sense of achievement. This may have contributed to the camera’s somewhat challenging operating concept, but its technology is beyond reproach.

Size and weight

When it comes to miniature cameras, size and weight must of course be given the highest priority. What else could be the motivation for using such cameras? All three cameras are so small that they can be held in one hand.

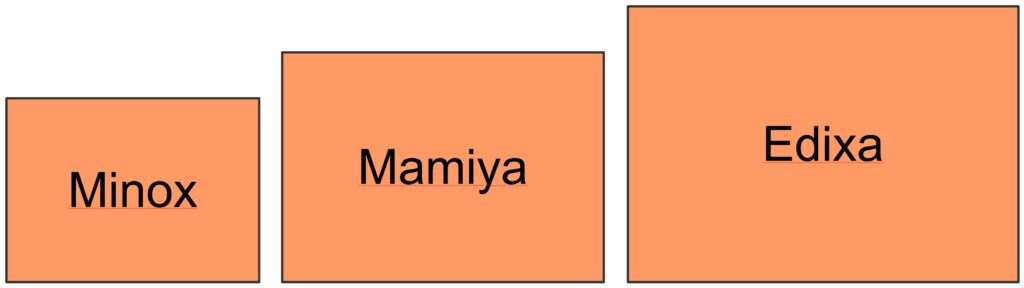

Nevertheless, there are significant differences in both size and weight. The Minox is by far the smallest. It can easily be hidden in the palm of your hand, just as Walter Zapp envisioned from the beginning. The other two cameras also fit in one hand, but they don’t disappear into it. They are easily twice the size. Nevertheless, they are still very small cameras.

Size

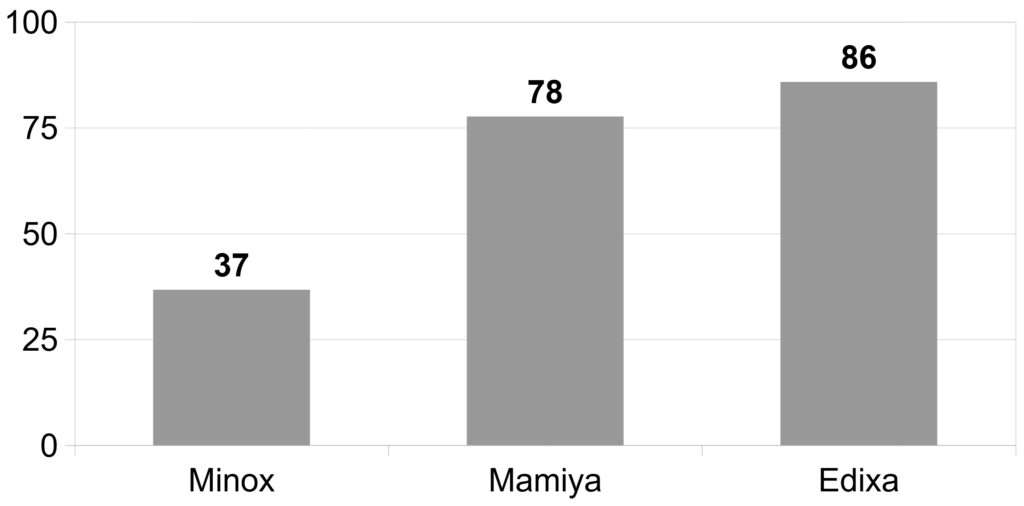

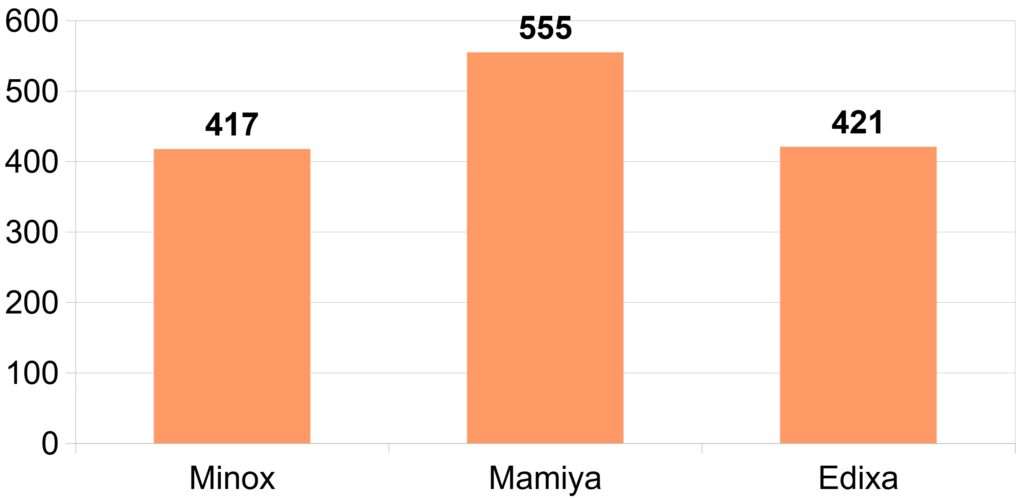

I consider the size to be the volume of the cameras, measured in cm3. I do not use the “official” dimensions, as these are overall measurements that also take into account small protruding parts. I have remeasured the cameras myself to obtain the actual volume. My volume specifications are therefore smaller, but more realistic.

As the photos suggest, the Minox is unbeatably small. The other two are about twice as large.

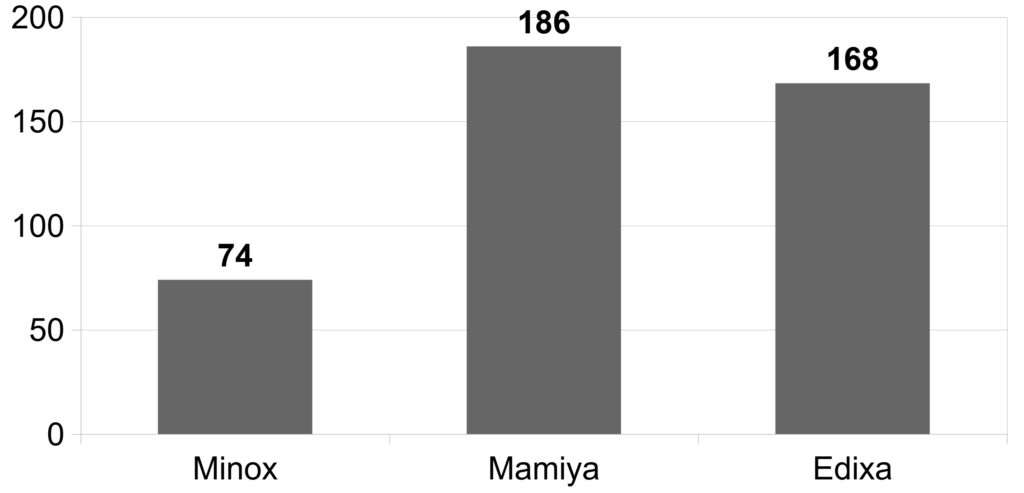

Weight

Minox again is the clear leader in terms of absolute values. However, if you relate the weight to the volume (the “density” of the camera), the Edixa is on par with the Minox at 2 g/cm³. The Mamiya is slightly higher at 2.4 g/cm³.

Of course, absolute size and weight are certainly decisive factors when you are out and about with your camera and carrying it in your pants or jacket pocket. However, you also have to take into account what you will ultimately achieve in terms of photographic results. In addition to image quality—which will be discussed later—the negative format is an important parameter. This is because, especially with miniature formats, it can be a limiting factor when enlarging images.

As you can see, the negative frame size differs considerably between the three models. The Mamiya (10 x 14 mm) has 60% more surface area, while the Edixa (12 x 17 mm) has more than twice that of the Minox (8 x 11 mm).

I have therefore compared the size of the cameras (volume) to the size of the respective negative format. This parameter allows conclusions to be drawn about the quality of the designs. The smaller the number, the larger the negative you get relative to the camera’s size.

Minox and Edixa have roughly the same values, meaning both provide a similar frame size relative to their camera volume. The Mamiya’s ratio is about 32% higher. This indicates that its larger size does not result in a proportionally larger negative.

Conclusion on size and weight

The three cameras are comparable, but still significantly different. Minox is clearly ahead in terms of absolute values. The Edixa is on par when you take into account the much larger negative format. The Mamiya is significantly larger and heavier than the Minox without offering a correspondingly larger negative format.

Lenses

When it comes to optical properties, the lenses are of course crucial, both in terms of imaging performance and image composition. All three cameras have high-quality anastigmat lenses with 4 lenses in 3 groups.

All three cameras focus by moving the entire optical assembly of the lens relative to the film. This is called “unit focusing,” as opposed to moving only a front or rear lens element. This method often provides better optical performance across the entire focus range.

- Minox: 15 mm, f1:3.5

The Complan lens is optimized so that the negative does not have to be pressed flat, but rather in a spherical shape, in order to achieve even better performance. This takes into account the extremely small negative format. - Mamiya: 25 mm, f1:3.5

Mamiya super 16 is fitted with a high quality hard coated Sekor lens developed and manufactured by Mamiya. - Edixa: 25 mm, f1:2.8

Edixa’s Xenar lens produced by Schneider-Kreuznach maintains high contrast and edge-to-edge sharpness, characteristic of the well-established Xenar optical formula used across various formats.

Focal length

The focal lengths, which range from 15 to 25 mm, are relevant for image composition. However, since the three models have different negative formats, these figures are not meaningful. Instead, it makes more sense to compare them with the corresponding 35 mm focal lengths, especially since this is easier to visualize.

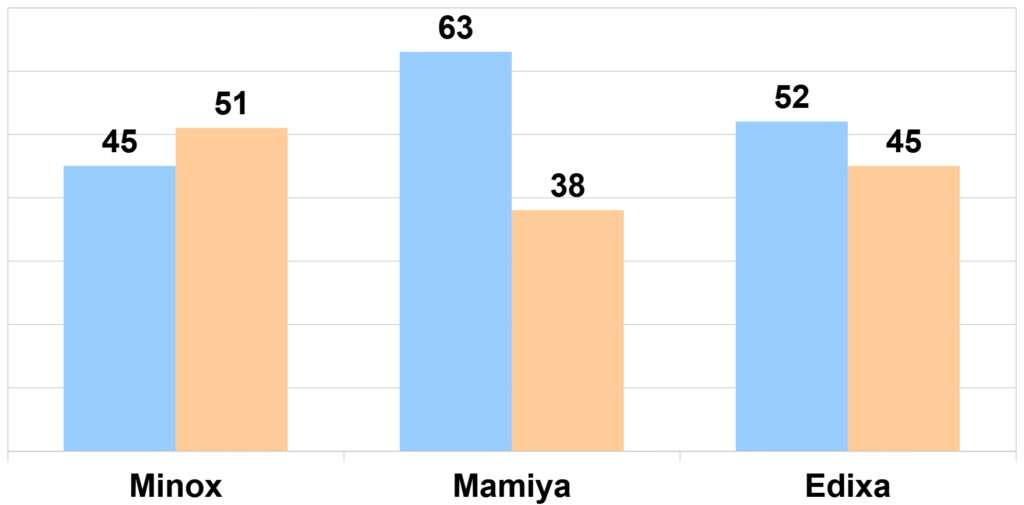

As you can see, the Edixa comes closest to a standard lens with a focal length of 52 mm. The Minox has a slightly larger image angle at 45 mm, while the Mamiya is in the slight telephoto range at 63 mm. All focal lengths are converted to 35 mm format. This is also clearly noticeable when looking through the viewfinders.

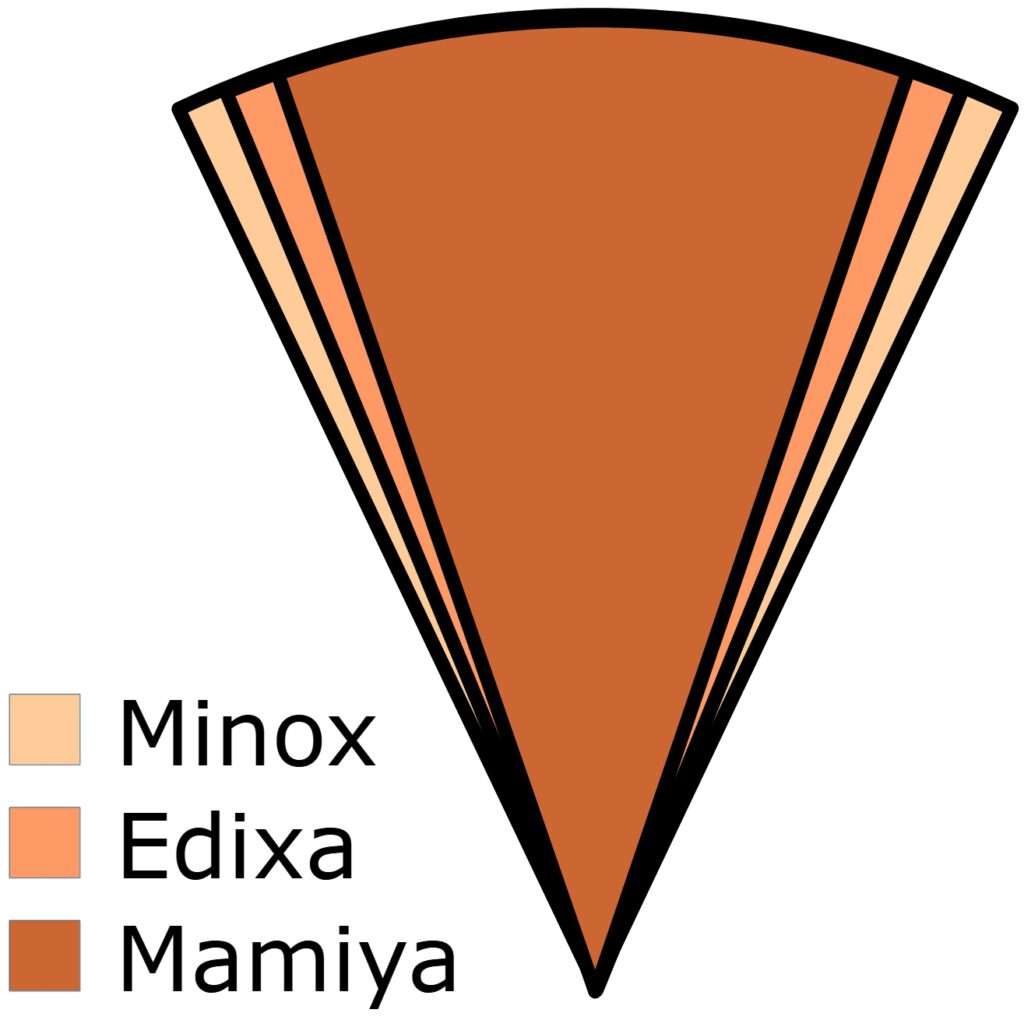

Angle of view

The corresponding diagonal angles of view are also interesting. To illustrate how little they differ from each other, here are the values (51°, 45°, 38°) from the diagram visualized:

Resolution

In photography, resolution describes the ability of a lens to transfer the finest details of a subject to the film separately from each other.

Since, to my knowledge, no systematically measured resolutions have been published for any of the three cameras, I took measurements myself. This allows for objective comparison of the values. The measurements provide resolution values in LP/mm for the center of the image and the four corners.

f you are interested how I determined the resolutions, here is my test procedure for the three cameras:

A combined test chart (Siemens star, USAF 1951, gray scale) was photographed at a distance of 1 m for all cameras. The resolution in the center of the image was determined using the Siemens star, and that in the corners of the image using the USAF chart.

To minimize the influence of film grain, I used ADOS CMS 20 II, the finest-grained film available. Exposed at ISO 12, developed for 10 minutes at 23 °C with ADOTECH IV.

To prevent motion blur, I took all photos with a flash (Vivitar 273 electronic flash, manual mode, 1/1000 s).

The shooting distance was 1 m, measured with a ruler. The parallelism of the image and film planes was established with four distance measurements to the corners of the test chart.

With the Minox, I used the (only available) aperture of f3.5, with the Mamiya and Edixa, f5.6.

I evaluated the negatives using an Edmund Optics microscope at 50x magnification.

If you want to learn more about testing lenses at home, read my article on the subject.

Theoretical resolution

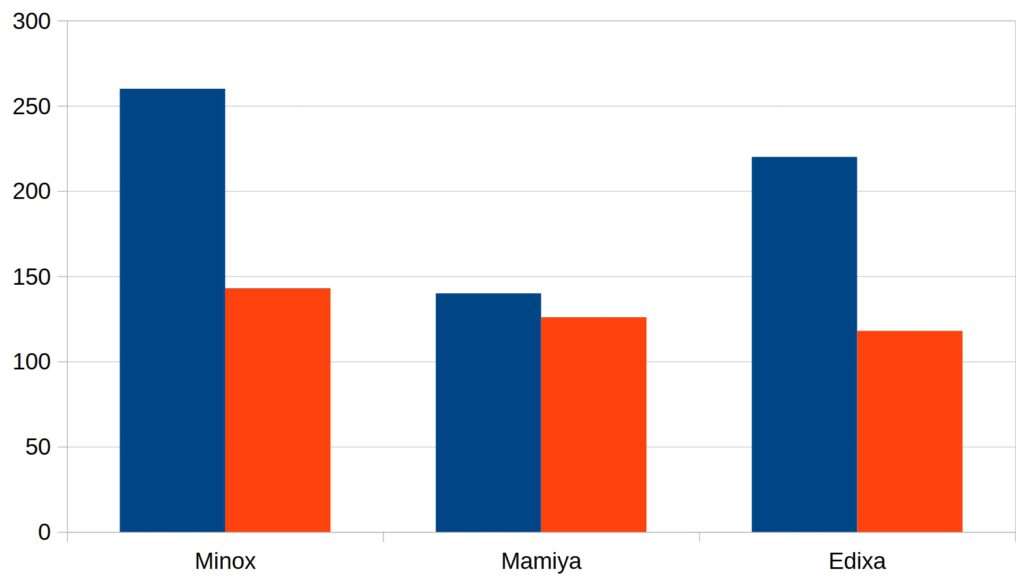

The lenses of the three cameras are very high quality, but vary in terms of resolution. A common measure is the number of line pairs per millimeter (LP/mm). Here we see the resolution of each lens measured by me in the center and at the edge:

What is striking about the Mamiya is that the resolution at the edges of the image is almost as good as in the center. This is exceptionally good for lenses of this design. The other two cameras have much higher resolution in the center of the image, but drop off sharply towards the edges. Nevertheless, the resolution at the edges of the Minox is still better than that of the Mamiya in the center of the image.

If we take the arithmetic mean between the center of the image and the corners of the image as comparative values, we get the following values:

- Minox 202 LP/mm (center 260, corners 143)

- Mamiya 133 LP/mm (center 140, corners 126)

- Edixa 165 LP/mm (center 220, corners 118)

If you are surprised by these high values, please note that we are talking about high-quality cameras with very small lenses. The effective diameters of the lenses are less than 9 mm (Minox 4.3 mm, Mamiya 7.1 mm, Edixa 8.9 mm).

When comparing the values with the resolutions of other lenses, make sure that you are looking at the theoretical resolution. Often, a much lower system resolution is specified in connection with a film; see the next section.

For some of us, it may be helpful to convert the resolution values into megapixels. This results in the following theoretical values:

- Minox 19.2 megapixels

- Mamiya 13.2 megapixels

- Edixa 29.6 megapixels

How do I calculate megapixels?

You can find more information here.

Practical resolution

However, the resolution of the lens alone does not say anything about the resolution of the negative. In most cases, the resolution of the film material is the limiting factor.

The resolution of the negative rsystem is then calculated from the resolutions of the lens rlens and the film rfilm as follows

The system resolution of a camera is therefore composed of the resolution of the lens and the resolution of the film used.

A high optical (arial) lens resolution is therefore only useful if a film with a correspondingly high resolution is used. The lower the film resolution (graininess), the less a high-quality lens can demonstrate its strengths. This has serious consequences in practice.

Even an ultra-high-resolution film such as ADOX CMS 20 II, which I used for my tests, significantly reduces the system resolution of the cameras. It reduces the theoretical resolution, for example, from 202 to 144 LP/mm in the Minox.

The Kodak Ektar 100, currently the finest-grained color negative film, dramatically reduces the theoretical resolution, e.g., in the Minox from 202 to 69 LP/mm.

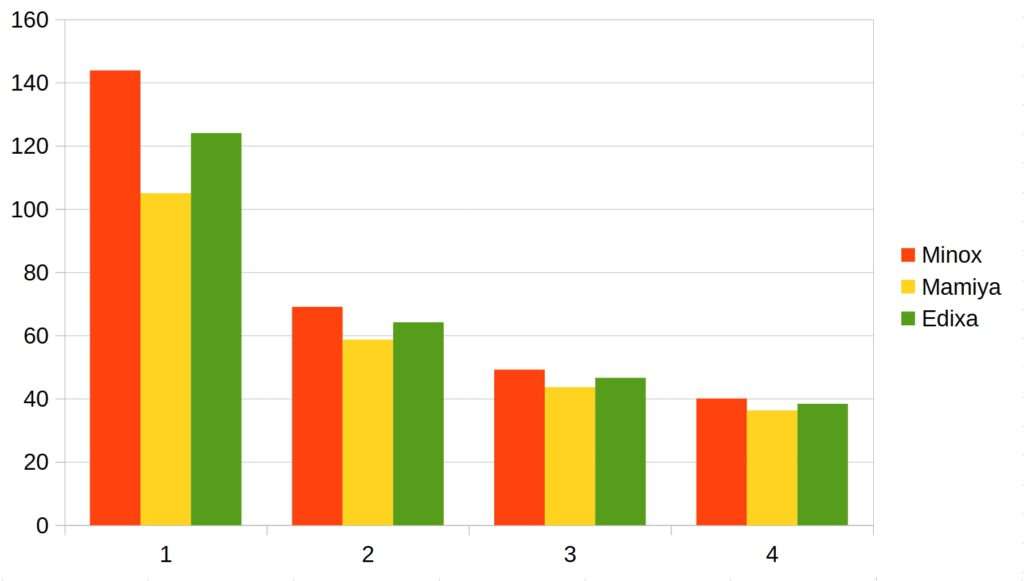

The following diagram shows the system resolutions of the three cameras with different films:

1: ADOX CMS 20 II, measured values [500 LP/mm]

2: Kodak Ektar 100, measured values [105 LP/mm]

3: Vintage Agfa Isopan 100, estimated values [65 LP/mm]

4: Vintage Agfacolor CN 17, estimated values [50 LP/mm]

It is apparent that, except for the ADOX CMS 20 II, the cameras have almost the same resolution. It can be seen that, with the exception of the ADOX CMS 20 II, the cameras have almost the same resolution. The differences between the cameras are less than 15 %. With the typical films used in the past, the difference was even smaller.

Conclusion on the resolution

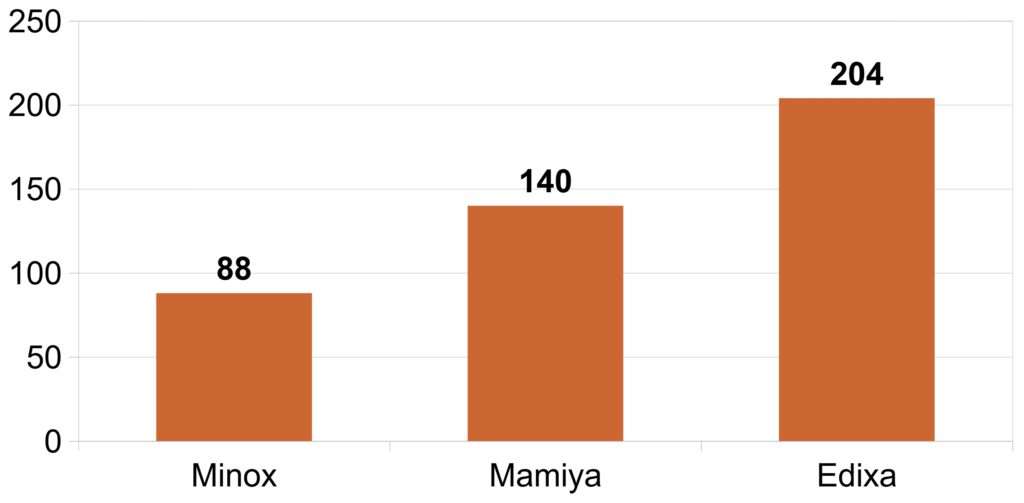

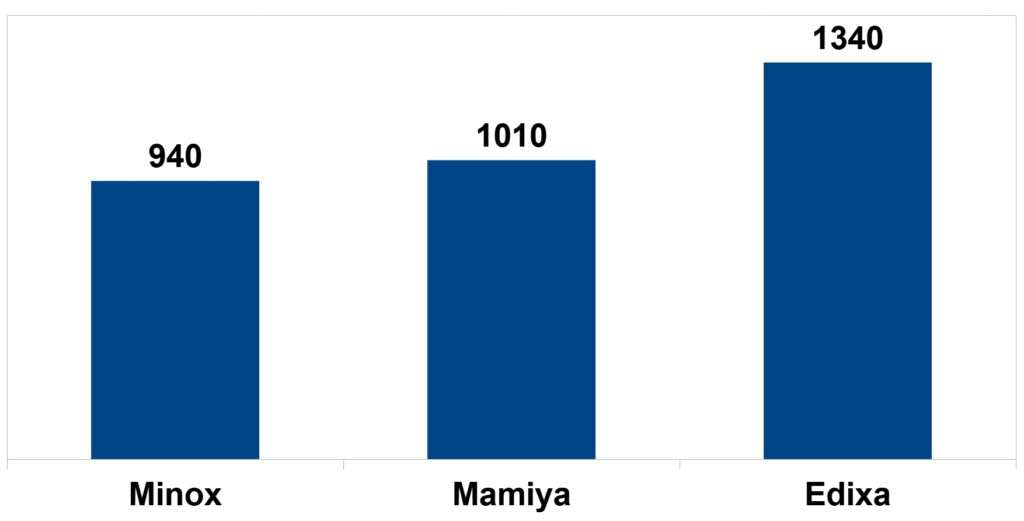

Now let’s compare the resolutions that can be expected from the three cameras in practical application. As a benchmark, I will use the combined resolution of the lens and film, as shown in the diagram above, multiplied by the respective negative diagonal. This value indicates how many line pairs the negative contains.

The higher this value, the more detail can be reproduced in the final image, provided that the images from the three cameras are enlarged to the same paper format. The same applies when scanning the negatives and digitally post-processing them. The following diagram shows how many line pairs the respective negative can record on a Kodak Ektar 100:

The Edixa is way ahead thanks to its large negative format. Despite its outstanding lens, the Minox cannot keep up due to its small negatives. For the same reason, the Mamiya is slightly superior to the Minox.

Close-Ups

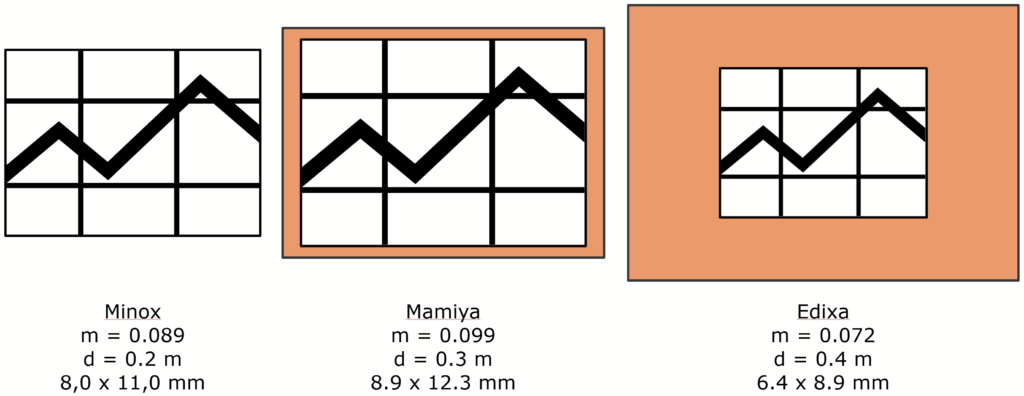

How well do the three cameras capture small objects? It makes sense to refer to the close-focus settings, i.e., the shortest distance at which the camera can be adjusted. For the Minox, this is 0.2 m, for the Mamiya 0.3 m, and for the Edixa 0.4 m.

One might therefore assume that the Minox takes the best close-ups. But that’s not true. Why?

As we have already discussed, the cameras have different focal lengths and use different negative formats. Both of these factors have a decisive influence on the answer to our question. Theoretically, differences in lens quality (resolution) could also have an impact. Even though the Minox lens clearly stands out among these three lenses, the other two are also good enough that this influence can be disregarded.

The decisive factor is how large a given section of the object appears on the negative when focusing at the closest distance.

In photography, the magnification ratio is denoted by m. It indicates the ratio between the size of the image on the negative and the actual size of the object. A reproduction ratio of 1 means that the object is projected onto the negative in its original size. Smaller values mean that the object appears smaller on the negative.

The magnification ratios are Minox: 0.0889, Mamiya 0.0988 and Edixa 0.0716.

Let’s take the Minox as a benchmark here. The smallest object area it can capture is 90 x 124 mm at a distance of 0.2 m. This section of the image would fill the Minox negative exactly. Let’s now see how large this section would appear on a Mamiya and an Edixa negative if the shortest distance were set on each. The following picture shows an object area of 90 x 124 mm represented on the negative (m: magnification ratio, d: distance, a x b: negative area):

As you can see, the object area is largest on the Mamiya negative. Because it uses the most amount of film, enlarging it later will produce the best quality.

Surprisingly, the Mamiya captures small objects with the highest resolution. The Edixa is the least suitable for this purpose. It cannot exploit the strength of its large negative format at close range. The Minox comes in second place, just behind the Mamiya.

You may want to know how I calculated the size on the negative with which the image section is reproduced. You can find the physical and mathematical derivation here.

To calculate the size on the negative, the magnification ratio m is required. This is calculated from the focal length f and the total distance d (object to film plane) via the image distance b.

𝑓: Focal length of the lens.

𝑑: Total distance from the subject to the film plane (the “Focus” setting).

𝑔: Object distance (Subject to Lens).

𝑏: Image distance (Lens to Film).

Fundamental lens equation:

With

From a geometric point of view, only the minus branch can be considered.

Magnification ratio:

Example for Minox A (f = 15 mm, d = 200 mm):

Exposure systems

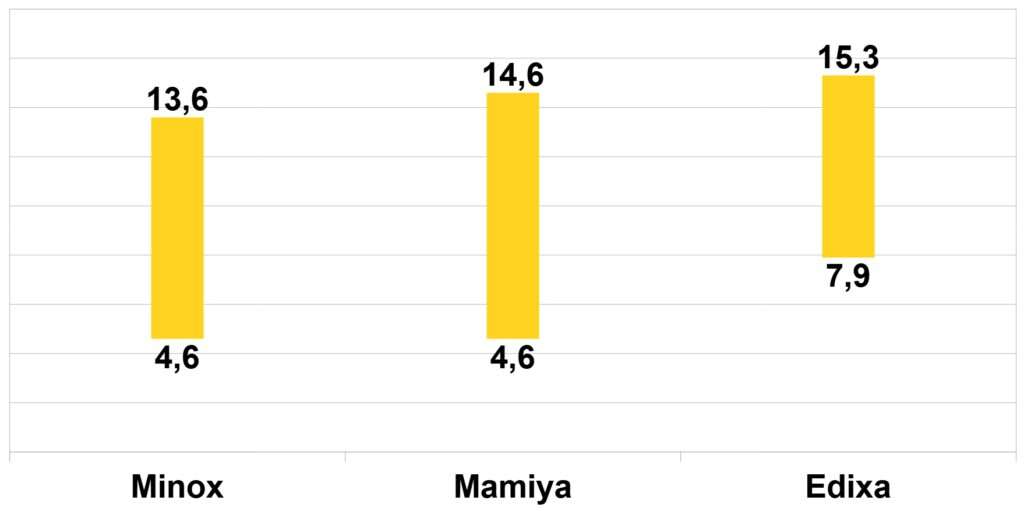

The EV light values covered by the cameras are almost identical for Minox (EV 4.6…13.6) and Mamiya (EV 4.6…14.6). Despite its fast lens (f2.8), the Edixa only starts at EV 7.9 and ends slightly higher at EV 15.3.

With Minox, the upper limit can be extended even further on some models with the built-in ND filter.

If, for practical purposes, we only consider exposure times that can still be photographed handheld, all cameras are once again on a level playing field. The EV range then starts at EV 8.0 for the Minox (1/20 s), EV 8.3 for the Mamiya (1/25 s), and EV 7.9 for the Edixa (1/30 s).

Apertures

In terms of aperture range, the Minox has a design disadvantage with its fixed aperture of 3.5. The Edixa has the largest aperture range with f2.8 to f16, while the Mamiya is below this with f3.5 to f11.

Here we are only considering the creative aspect; we have already discussed the influence of the aperture on exposure above. In subminiature photography, playing with the aesthetic quality of blur is a challenge due to the small negatives:

The maximum aperture of f/2.8 (Edixa) or f/3.5 (Mamiya) and the longer focal length of 25 mm allow visible bokeh to be achieved in close-ups. The background blurs gently, which makes subjects stand out vividly from the background.

With the Minox, pronounced bokeh is hardly possible because the extremely short 15 mm focal length physically produces an almost infinite depth of field. Only at extremely close range (e.g., 20 cm) does the background become slightly blurred, but it usually remains recognizable.

Shutter speeds

The camera shutter is widely considered the most mechanically demanding and complex component of an analog camera. While lenses are largely static optical systems, the shutter is a high-performance machine that must operate with absolute precision under extreme physical stress.

A shutter must accelerate from a standstill to its maximum speed within milliseconds and, even more critically, come to a dead stop without any vibration or “bounce.” The mechanical timing unit (the “escapement”) must govern two entirely different physical behaviors:

High Speeds: In a Minox firing at 1/1000s, the tiny mechanical components endure massive G-forces.

Slow Speeds (e.g., 1/2s): A gear train, similar to the movement of a mechanical watch, must precisely delay the closing of the shutter. These gears must remain perfectly synchronized and functional over decades of use.

Ranges of shutter speeds

- Minox

The Minox offers the most versatile shutter speed range, spanning from 1/2 s to 1/1000 s. This extensive range is a technical necessity, as the camera operates with a fixed aperture of f/3.5. Without the ability to stop down the lens, the fast 1/1000 s shutter speed is the primary tool for managing bright light conditions.

- Mamiya

The Mamiya falls slightly below the Minox in terms of speed, offering a range from 1/2 s to 1/200 s. However, it effectively compensates for the lack of a very fast shutter speed through its adjustable aperture. By stopping the lens down to f/11, the camera can handle high-intensity light environments that would otherwise require much faster shutter speeds.

- Edixa

The shutter system is considered the greatest weakness of the Edixa 16. It provides only three speeds: 1/30, 1/60, and 1/150 s.

Standard Models: On basic versions, these speeds are mechanically linked to specific aperture values, severely limiting creative control.

The M-Model: This limitation does not apply to the Edixa 16 M considered here, which allows for independent setting of aperture and shutter speed, though it remains restricted by the narrow range of available times.

In a direct comparison, the Minox B offers the greatest range with 1/2 to 1/1000 s, which it absolutely needs to compensate for its fixed aperture. The Mamiya is below this with 1/2 to 1/200 s, but compensates for this flexibly with its adjustable aperture up to f/11. The Edixa brings up the rear: its only three speeds (1/30, 1/60, 1/150 s) limit it the most.