Immanuel Kant: What is Enlightenment?

Page Contents

Key points of Kant’s article

What is Enlightenment?

Immanuel Kant’s 1784 essay defines enlightenment as humans freeing themselves from “self-incurred immaturity,” meaning the inability to use their own understanding without guidance from others. This immaturity comes from laziness and cowardice, not a lack of ability, and Kant’s motto is “Dare to know!” encouraging independent thinking.

The Role of Freedom

Kant emphasizes that freedom, especially the freedom to use reason publicly is essential for progress. In private roles, such as soldiers following orders or citizens paying taxes, people must obey rules, but they can still critique these systems publicly.

Public vs. Private Reason

Kant distinguishes between public use of reason, where individuals can freely express ideas (e.g., writing or debating), and private use, where they must follow duties (e.g., a soldier obeying commands). Public freedom is key for enlightenment, while private obedience maintains order.

Progress and Criticism

Kant criticizes binding future generations with unchangeable religious rules, as it blocks progress. He praises rulers who allow public freedom, like Frederick the Great, seeing his time as an “age of enlightenment,” not fully enlightened yet, but moving forward.

Overall Message

Kant calls for courage to think independently, highlighting public discourse’s role in gradual societal progress toward rationality and autonomy.

Why this article is extremely topical

The progress of enlightenment since Kant’s time shows mixed results. The potential for independent thinking has grown with access to information and platforms, but intellectual laziness, exploited by opinion leaders, fact-checkers, and media, hinders advancement. Kant’s vision requires active, critical engagement, yet current trends suggest that without widespread commitment to “daring to know,” we remain in an extended “age of enlightenment” rather than achieving an enlightened age.

The digital age has expanded Kant’s “public use of reason.” Platforms like social media enable widespread discourse, aligning with Kant’s call for free public expression. Fact-checkers, when used as tools for verification, empower individuals to question narratives, reflecting Kant’s emphasis on independent reason. Diverse media outlets provide access to multiple perspectives, theoretically fostering critical engagement.

However, intellectual laziness persists and is amplified. Opinion leaders exploit passivity by offering simplified narratives, discouraging scrutiny. Fact-checkers foster dependency if people accept their conclusions without understanding the process, undermining Kant’s call for self-reliant reason. Mainstream media’s framing, often influenced by corporate or political agendas, risks passive consumption. This mirrors Kant’s critique of those preferring guidance from authorities.

The full text of 1784

The most important part of the text is the first three sections. These describe the real problem for us as individuals. You have to read this part and think it through for yourself. Kant wrote this text in simple language (which is not something you can say about him otherwise).

In the rest of the text, he derives the conclusions for society and the state. This is politically relevant and anyone who is interested should read to the end, but otherwise you can stop after the first three sections. The bold highlights in the text there were made by me.

Translation into English

Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity (selbstverschuldeten Unmündigkeit). Immaturity is the inability to use one understanding without guidance from another. Self-incurred is this tutelage when its cause lies not in lack of understanding (Verstandes), but rather of resolve and courage to use it without direction from another. Sapere Aude! [Latin translated: Dare to know, from Horace]. Have courage to use your own mind ! Thus is the motto of Enlightenment.

Laziness and cowardice are the causes (Ursachen), why such a large part of humanity, after nature has released them from external guidance (natura liter maiorennes) [Latin translated: come of age via nature], remain; but like life immaturity, and why it is so easy to set themselves up as their guardians. It is so convenient to be immature. I have a book, which understands for me, a pastor who has conscience (Gewissen) for me, and a physician who decides my diet, etc., so I do not even need to try. I do not think, if only I can pay: others will readily undertake the irksome work for me. That by far the largest proportion of people (including the entire (ganze) fair sex), the step to maturity, but this is that it difficult, even for very dangerous to think, have rendered those guardians, the ultimate supervisor (Oberaufsicht) of them graciously took upon themselves. Once they have made their domestic cattle first stupid and have made sure that were these placid creatures will not dare step without the harness is it a like a children’s walking cart (Perreten), if they try it go alone it shows them the danger to them threatens. Now this danger is not so great, for they would learn to walk by falling a few steps times, but an example of this kind makes men timid and usually frightens them out of all further attempts.

So it is difficult for any single individual to work himself out of immaturity as has become almost his own nature. He has even grown fond and forehand is really incapable of his own use of his understanding (Verstandes), because you never let him make the attempt. Statutes and formulas, those mechanical tools of the rational use, or rather misuse, of his natural gifts, are the fetters of an everlasting immaturity (Unmündigkeit). Whoever throws them off would still do well on the narrowest trench only an uncertain leap, because he is not accustomed to kind of free movement. Therefore, there are few who have succeeded in extricate themselves by their own exercise of mind (Geistes) from immaturity and still a steady pace.

But that the public should enlighten itself is more possible, yes, it is; if one is only allowed freedom, Enlightenment is almost sure. For there will always be some independent thinkers (Selbstdenkende), found even among the established guardians of the great masses, who, after throwing off the yoke of immaturity themselves thrown to think the spirit of a reasonable estimate of their own worth and every man’s vocation, will spread even to themselves. Especially is herein: that the public, which previously brought by them under this yoke by them afterwards even, forces them to remain among them, when some of his guardians (Vormünder), who are altogether incapable of Enlightenment been incited to do so. Thus, harmful it is, to plant prejudices; for they finally take revenge on those themselves, or their predecessors have been their authors. Thus, a public can only slowly attain Enlightenment. A revolution is perhaps probably a waste of personal despotism or of avaricious or tyrannical oppression (herrschsüchtiger Bedrückung); but never a true reform in ways of thinking can come about; but rather, are new prejudices, just as well serve as the old ones to harness the great unthinking mass (gedankenlosen großen Haufens).

For this Enlightenment nothing is required but freedom, namely the most harmless amongst all what may be called freedom, namely: to make use of one’s reason (Vernunft) in all public use. But I hear calling from allsides: do no argue! The officer says: do not argue but rather drill! The tax collector: do not argue, but rather pay! The clergyman: do not argue, but rather believe! (Only one ruler in the world says: argue all you want and what you want, but obey (gehorcht)). Here is everywhere restriction (Einschränkung) of freedom. But which restriction hinders Enlightenment and which not, but instead actually advances it? – 1 answer: the public use of reason (Vernunft) must always be free, and it alone can bring about Enlightenment among men; the private use (Privatgebrauch) of reason may often be very narrowly restricted without particularly hindering the progress of Enlightenment. But I understand the public use (öffentlichen Gebrauche) of one’s reason, to anyone as a scholar makes of reason before the entire literate world. Private use I call that which he entrusted to him ina certain civil post or office shall make use of his reason. Is now to some businesses (Geschafte) that run in the interest of the community, a certain mechanism is necessary, by means of which some members of the community must passively conduct themselves in order, by an artificial unanimity, the government for public purposes or the destruction of at least held to these purposes. It is certainly not allowed to see reason alternative, but rather one must obey. If, however, this part of the machine [Translator note: German word is ‘Maschine’] at the same time as a member of a whole commonwealth, regards itself at the world civil society, and thus in the quality of a scholar who can addresses an audience at the proper sense of expediency alternate, however, without prejudice to the businesses suffering to which he is in part responsible as a passive member. So it would be very disastrous if an officer, who is commanded by his superior, was serving on the desirability or utility of a given to command — he must obey. He cannot be justly constrained from making a scholar of the error in

the military service notes and submit them to the public for their opinion. The citizen cannot refuse to pay the taxes imposed on them, indeed, impertinent criticism of such levies, if they are to be paid by them, as a scandal (occasion general insubordination) could be punished. However, the same person does not act contrary notwithstanding this the duty of a

citizen, when he publicly expresses his thoughts as a scholar resists the impropriety or even injustice of such tenders. Similarly, a clergyman is connected to do his catechism students and his community after the Church he serves his presentation symbol [Translator note: the German word is indeed: Symbol], for he has been accepting to this condition. But as a

scholar he has complete freedom, indeed even the calling to all his carefully tested and well-intentioned thoughts on the faulty in that symbol and suggestions for the better establishment of religion and Church being communicated to the audience. There is devised nothing that could be put to burden his conscience. For what he teaches as a result of his duties as business of the Church, which he presents as something, in respect of which he has not free of violence to teach as he sees fit; but rather that he is hired to carry forward provision for and in the name of another. He will say: our Church teaches this or that and these are the arguments, which he uses. He thus extracts all practical uses for his congregation from precepts to which he would not himself subscribe with complete conviction; but whose presentation he can nonetheless undertake, since it is not entirely impossible that truth lies hidden; but in any event, at least nothing of the inner religion contradictory fact is encountered. Because he believed he had found them, he would not administer his office with a conscience, and he would have to resign. The use, therefore, to an appointed teacher makes of his reason before his congregation is merely private, because this is only one home, however large meeting, and in respect of which he is a priest not free and should it not also be such because he is someone else. In contrast, as a scholar, who through his writings to his public; says the world, the clergyman in the public use of his reason enjoys an unlimited freedom to use his own reason and to speak in his own person. If the fact that the guardians of the people (in spiritual matters) should themselves be immature is an absurdity, which amounts to the perpetuation of absurdities (Denn dass die Vormünder des Volks (in geistlichen Dingen) selbst wieder unmündig sein sollen, ist eine Ungereimtheit, die auf Verewigung der Ungereimtheiten hinausläuft). But should not be a society of pastors, perhaps a Church assembly or a venerable classis (as they call themselves among the Dutch), authorized to commit itself by oath to a certain unalterable symbol in order to secure a

constant guardianship over each of its members and by means they lead over the people and to perpetuate this at all? I say this is altogether impossible. Such a contract (Kontrakt), whose intention is to shut off forever all further Enlightenment of the human race would be closed, is absolutely null and void and even if it should be confirmed by the supreme power, by parliaments, and the most solemn peace treaties. One age (Zeitalter) cannot bind itself and to conspire (verschworen), to put the following in a condition that it must be impossible for it to extent it (mainly so earnestly (angelegentliche)) knowledge of errors and clean all continuous writing (weiterzuschreiten) in the Enlightenment. That would be a crime against human nature, whose original determination (Bestimmung) lies precisely in such progress, and the offspring would be fully justified in rejecting those agreements as unauthorized and take

malicious manner to discard. Whether the people could themselves have imposed such a law: the touchstone of all that can be adopted as law by a people lies in the question? Now this would have to speak with the expectation of a better specific short period possible to introduce some order: one might let every citizen, and especially the clergy, freely and

publicly in the quality of a scholar, that is, make through his writings, on the erroneous of the present institution’s remarks. However, the newly introduced order might last until insight into the nature of these matters had so far and tried, that by uniting their voices (though not all) of a proposal could bring the throne to take those congregations under protection which

had united after their terms of better access to a changed religious organization, but without interfering with those who wanted to leave it at the same. But a persistent, some from anyone publicly doubting religion constitution even within the lifetime of a human, and thus destroy a period in the progress of mankind toward improvement, and is fruitless. But this

probably disadvantage even to make the progeny (Nachkommenschaft) is absolutely unauthorized. A man may for his person, and even then only for some time in what is for him to know, postpone Enlightenment; but to do it to renounce it for himself, but even more for posterity, is the sacred violate human rights and get trampled underfoot (FuBen). But what may not decree a people by themselves may still less by a monarch, the people, for their legal authority rests on the fact that it unites the entire people’s will (Volkswillen) in their own. If he only sees to it that all the real or perceived improvement there with the civil order: he may demonstrate to his subject’s salvation sake by the way can only make themselves necessary what they are doing. This does not concern him, but rather to prevent, lest any other violent is prevented, in the provision and delivery the same to work his fortune after all. He does even his majesty crash when he mixes in this, since the writings, which seek to bring his subjects

their insights into the pure, evaluate his own governance, he does this on his own highest insight, where he lays upon himself the reproach: Caesar non est supra Grammaticos [Latin translated: Caesar is not above the grammarians], as well. It is still more when his supreme authority as far humbled, to support the spiritual despotism of some tyrants in his state over

his other subjects.

When we are asked now: are we now living into an enlightened age? Then answer is: No (Nein), but in an age of Enlightenment. That the people, as matters now stand, in the whole (Ganzen), would have been able to or could be reduced only in religious matters are using their own understanding without direction from another secure and good to use, it is

still missing a lot. The very fact that now being opened for the field to deal with these things and that the obstacles (Hindernisse) to general Enlightenment or the release from their self-imposed immaturity is gradually less, of which we have clear indications. In this regard, this age is the age of Enlightenment or the century of Frederick (In diesem Betracht

ist dieses Zeitalter das Zeitalter der Aufklärung, oder das Jahrhundert Friederichs).

A prince (Ein Fiirst), who finds it not unworthy, that he considered it a duty in matters of religion prescribe nothing to men; but rather to allow complete freedom while renouncing the haughty name of tolerance, is himself enlightened and deserves to be praised by a grateful world and posterity as the first to the sexual immaturity of the human race, proposed

(vorschlug) at least part of the government, and each was free to operate in all matters of conscience to his own reason. Under him venerable clergy (Geistliche) are allowed, regardless of their official duties, they from the accepted symbol here or there different judgments and insights into the quality of the scholars freely and publicly explain the world for testing; but

much more than any other, which is restricted by no official duties (Amtspflich). This spirit of freedom spreads beyond this land, even where external obstacles to a misunderstanding their own government is struggling; because this is illuminated by the example that was at liberty to procure for the public peace (öffentliche Ruhe) and not in the least the unity of the commonwealth. People gradually work their way little by little from rudness (Roheit) of their own accord if only one does not deliberately to keep them in it. (Die Menschen arbeiten sich von selbst nach und nach aus der Roheit heraus, wenn man nur nicht absichtlich künstelt, um sie darin zu erhalten).

I have the main point (Hauptpunkt) of Enlightenment, that is [d.i.], the escape of men from their self-imposed immaturity, especially set in matters of religion: because in respect to the arts and sciences, our rulers (Beherrscher) have no interest in playing guardian over their subjects, moreover, even those immaturity, as is the most harmful, so even the most degrading of all. But the thinking of a head of state who favors religious Enlightenment goes even further and sees: that even in regard to its

legislation, there is no danger of allowing his subjects to exercise their own

public reason use and their thoughts concerning better formulations of the

same even with a frank criticism of the already given, before the public

world, of which we have a shining example wherein no monarch surpasses

the one whom we venerate [Translator note: or, ‘worship’, or, ‘adore’; the

German word is ‘verehren’].

But only one who is himself enlightened, is not afraid of shadows, at the

same time, however, has a well-disciplined and numerous army to

guarantee public peace, can say what no free state (Freistaat) may dare,

namely: argue all you want, and about what you want; but obey! It appears

here is a strange, unexpected transition in human affairs, as well as

elsewhere, when you look at it in the large, in which almost everything is

paradoxical. A greater degree of civil freedom seems advantageous to a

people freedom of thought and yet it places inescapable limitations, a lesser

degree of contrast gives this room, all fully to expand its capacity. If,

however, that is the hillside and work for free thinking is unwrapped, the

nature of this hard shell, the germ, for which it makes most fondly: so does

this return gradually to the temperament (Sinnesart) of the people (which

this act of freedom gradually is enabled). Finally even to the principles of a

government [Translator note: or regime (Regierung)], which itself is would

provide conducive to them, the man who is now more machine than as to

treat their dignity.

Königsberg in Prussia, 30 September, 1784

Translation copyright ©2013 Daniel Fidel Ferrer.

All rights reserved. Free unlimited distribution.

Creative Commons General Public License “Attribution, Non-Commercial”, version 3.0 ( CCPL BY-NC ).

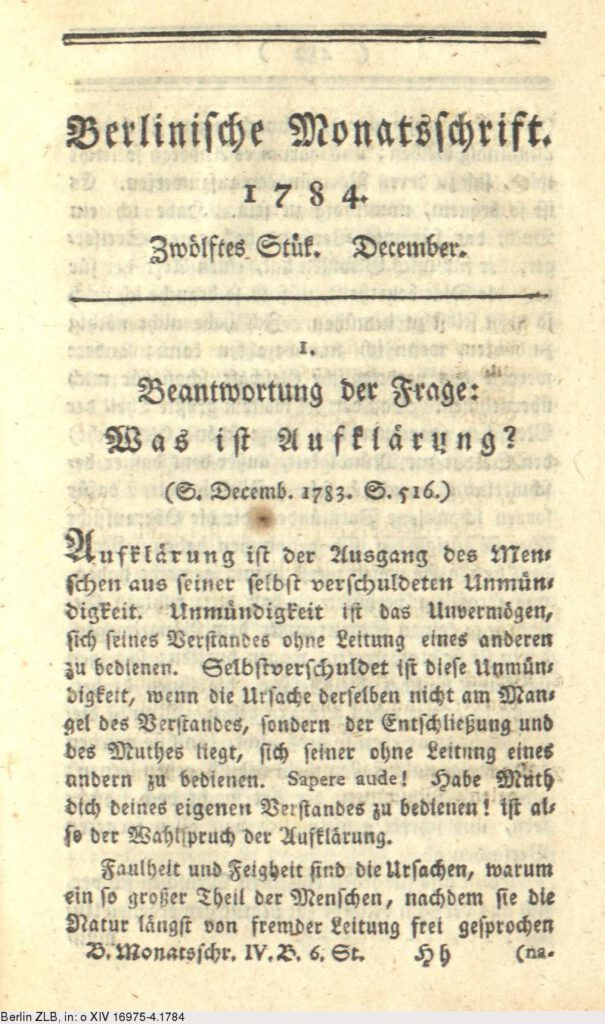

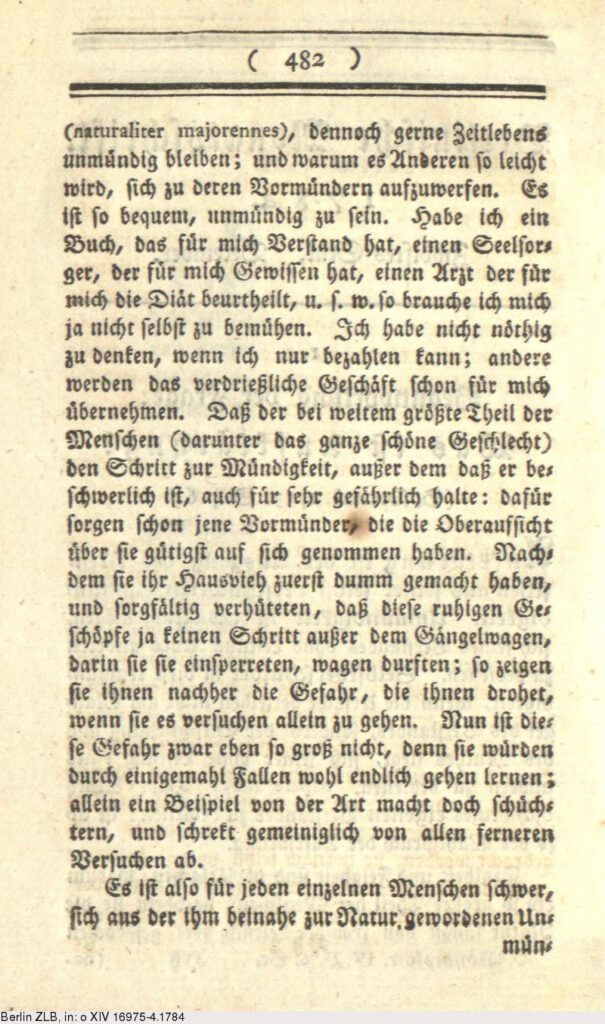

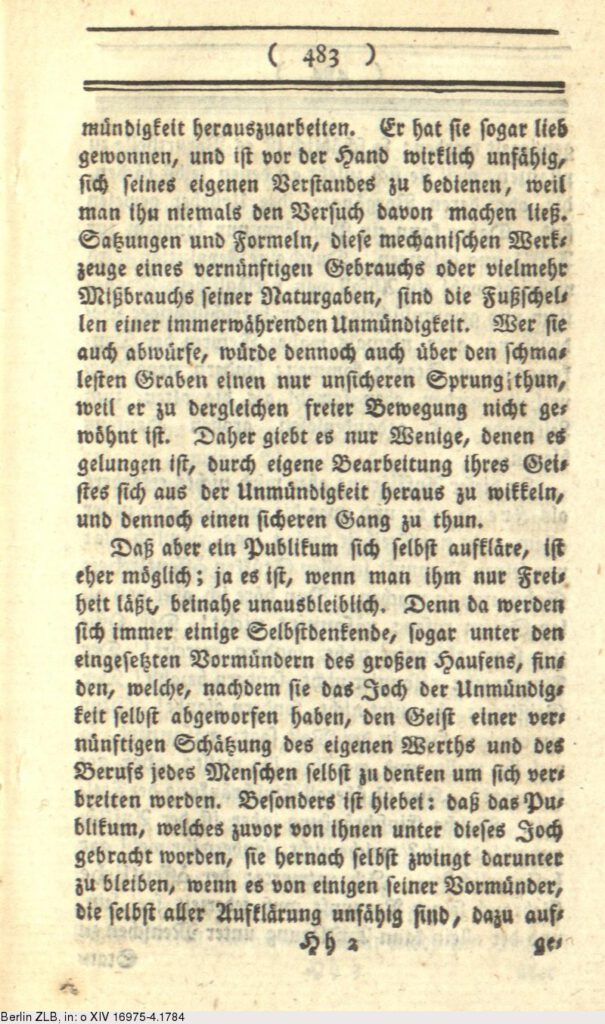

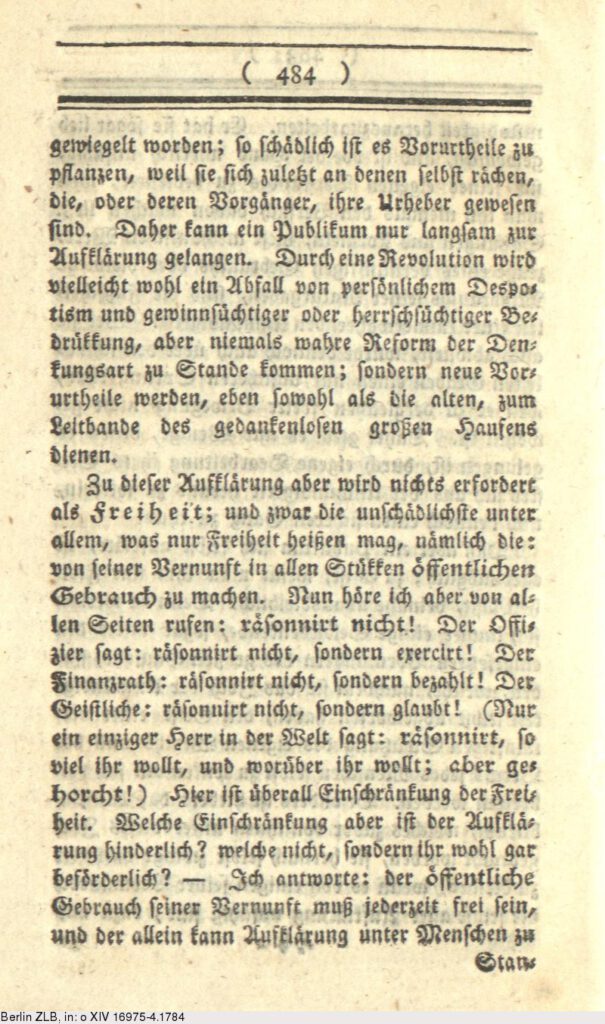

The original German text as a facsimile

Kant, Immanuel: Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung? In: Berlinische Monatsschrift, 1784, H. 12, S. 481-494. In: Deutsches Textarchiv https://www.deutschestextarchiv.de/kant_aufklaerung_1784, abgerufen am 16.04.2025.

Licence: Creative-Commons-Lizenz